Summary:

This article explores the complex and influential harmonic concept known as "Coltrane Changes." We will deconstruct this revolutionary chord progression, examine its theoretical underpinnings, and provide practical examples with audio and sheet music for aspiring jazz musicians. Understanding Coltrane Changes is a key step in mastering modern jazz harmony and improvisation, offering a powerful tool for harmonic sophistication.

Keywords:

Coltrane Changes, John Coltrane, Giant Steps, Jazz Harmony, Music Theory, Harmonic Progressions, Chord Substitution, Jazz Improvisation, Major Thirds Cycle, Sheets of Sound

Introduction:

In the late 1950s, the world of jazz was forever altered by the sound of one man: saxophonist John Coltrane. His torrents of notes, famously dubbed "sheets of sound," were fueled by a relentless exploration of harmony. At the heart of this exploration was a groundbreaking chord progression that has since become a rite of passage for jazz musicians: the Coltrane Changes. More than just a sequence of chords, it represents a new way of navigating musical space—a symmetrical and logical system that is as challenging as it is beautiful. This article will guide you through this fascinating harmonic maze, from its theoretical foundation to its practical application.

Definition and Classification:

Coltrane Changes, also known as the "Coltrane Matrix" or "Coltrane Cycle," is a harmonic progression that divides the octave into three equal parts. This creates a system of three key centers separated by major thirds. For example, starting from B major, the other two key centers are G major and E-flat major, forming a symmetrical triangle across the twelve tones of the chromatic scale.

The progression moves rapidly through these tonal centers, with each new tonic (Imaj7) being introduced by its corresponding dominant chord (V7). This creates a chain of V7-I resolutions that pull the listener through the different keys. This structure is often classified as a form of non-functional harmony, not because it lacks V-I motion, but because its overall architecture is based on a geometric pattern (the major thirds cycle) rather than the traditional circle-of-fifths movement that underpins most functional harmony.

Core Examples

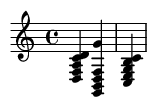

Example 1: The Basic "Giant Steps" Cycle

The most famous application of Coltrane Changes is the opening of his tune "Giant Steps." The progression moves through three key centers a major third apart (B, G, and Eb) before returning. Notice how each Major 7th chord is preceded by its Dominant 7th, creating a constant sense of forward motion.

Analysis:

- Bar 1: Starts in B major (Bmaj7) , then moves to its dominant (D7), which resolves to...

- Bar 2: G major (Gmaj7). This is followed by its dominant (Bb7), which resolves to...

- Bar 3: Eb major (Ebmaj7). We have now completed the cycle of three keys: B -> G -> Eb.

- Bar 4: The F#7 (V7 of B) sets up the return to the starting key of B major.

Practical Applications and Improvisation

Application: Substituting Over a Standard Progression

A powerful way to use Coltrane Changes is to superimpose them over a simpler, more static harmony. For example, a standard ii-V-I progression that ends on a long Cmaj7 chord can be transformed. Instead of holding Cmaj7 for two bars, you can insert a Coltrane cycle that resolves back to C.

Original Progression (Standard ii-V-I):

With Coltrane Substitution:

Explanation: After landing on Cmaj7, we immediately launch a cycle based on the key centers C, Ab, and E. The final Emaj7 chord (the III chord in C Major) smoothly leads back to chords in the original key, such as Dm7 or Am7. This adds incredible harmonic density and interest to an otherwise simple progression.

Improvisation Strategies

Navigating these changes is a challenge. Here are a few fundamental approaches:

- Arpeggios: The most direct approach is to outline each chord with its arpeggio (1-3-5-7). This builds muscle memory and helps your ear connect the melodic line to the underlying harmony.

- The "1-2-3-5" Pattern: A classic Coltrane-ism. For each chord, play the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th degrees of its major scale. For a Bmaj7 chord, this would be B-C#-D#-F#. For the following D7, you could play D-E-F#-A. This creates a flowing, scalar line that follows the changes perfectly.

- Connecting Tones: Look for the smoothest voice-leading between chords. The 3rd of one chord often resolves by a half-step to the 7th of the next, or vice-versa. Finding these connections will make your lines sound more logical and less like a series of disconnected arpeggios.

Historical Figures:

The undisputed pioneer of this sound is John Coltrane (1926-1967). His harmonic concepts were the result of intense personal study throughout the 1950s. His work with Thelonious Monk, whose compositions often featured angular melodies and unorthodox harmonies, and his later studies with theorist George Russell, were profoundly influential. Coltrane developed these changes while a member of Miles Davis's First Great Quintet but began to fully realize them on his 1960 album, *Giant Steps*. The album became a landmark in jazz history, establishing a new benchmark for technical and theoretical mastery that continues to influence musicians today.

Fun Facts:

For decades, improvising over the chord changes to "Giant Steps" has been considered "the ultimate test" for a jazz musician's harmonic knowledge and technical facility. Even the world-class musicians on the original 1959 recording session found it challenging. Pianist Tommy Flanagan's solo on the track is legendary, but he later admitted to being somewhat unprepared for the tune's difficulty and speed. Coltrane had reportedly practiced the progression relentlessly on both saxophone and piano for months leading up to the session.

Conclusions:

Coltrane Changes are more than a historical curiosity; they are a fundamental part of the modern jazz vocabulary. By systematically breaking away from traditional harmony, John Coltrane opened up a universe of new melodic and harmonic possibilities. While mastering these changes requires dedication, the process itself is a powerful ear-training and theory exercise. It forces you to think in multiple keys at once and to see the fingerboard or keyboard in a new, symmetrical way. How might you apply this principle of symmetrical division to other musical elements in your own playing, such as rhythm or melody?

References:

Porter, L. (1999). John Coltrane: His Life and Music. University of Michigan Press.

Levine, M. (1995). The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.

Berliner, P. F. (1994). Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press.

Historical Context and Musical Significance

Coltrane Changes emerged during John Coltrane's transformative period (1959-1960), epitomized by his landmark album Giant Steps. This harmonic system represented a radical departure from conventional ii-V-I progressions by cycling through three tonal centers connected by major third intervals (e.g., B→G→E♭). The approach was influenced by Nicolas Slonimsky's Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns and Coltrane's collaborations with theorists like Yusef Lateef. Its significance lies in creating heightened tension/release cycles and enabling unprecedented harmonic density – a core element of Coltrane's "Sheets of Sound" technique. This innovation expanded jazz's harmonic vocabulary, influencing generations of composers from McCoy Tyner to contemporary artists like Kamasi Washington.

Progressive Exercises

Beginner

Practice the core progression in one key: | Bmaj7 | D7 | Gmaj7 | B♭7 | E♭maj7 |. Use root-position triads in quarter notes (B-D-G-B♭-E♭). Focus on smooth voice leading. Record yourself looping this and improvise using only chord tones.

Intermediate

Cycle through all three keys in 12-bar form: | Bmaj7 D7 | Gmaj7 B♭7 | E♭maj7 | Am7 D7 | (repeat). Improvise using scale fragments: B major over Bmaj7, D mixolydian over D7, etc. Transpose to minor keys (e.g., E♭→G→B minor).

Advanced

Apply substitutions over "Giant Steps": Replace | Bmaj7 D7 | with | Emin7 A7 | Dmaj7 | (ii-V of D). Improvise at 240+ BPM using pentatonic superimpositions (e.g., G minor pentatonic over B♭7). Compose a 16-bar tune using secondary dominants within the cycle.

Ear Training Tips

Internalize the sound through targeted listening:

- Chord Progression ID: Use apps like iReal Pro to isolate Coltrane changes (e.g., "Giant Steps" at 50% speed). Sing root movements (B→G→E♭) against drone tones.

- Transcription: Analyze Coltrane's "Countdown" solo, noting how he outlines the changes using 3rds/7ths. Transcribe the voice leading in McCoy Tyner's comping.

- Singing: Scat-sing the arpeggiated progression: B-D-F♯-A (Bmaj7) → D-F♯-A-C (D7) → G-B-D-F♯ (Gmaj7). Gradually increase tempo.

Common Usage in Different Genres

While rooted in jazz, Coltrane Changes appear across genres:

- Fusion: Frank Zappa's "King Kong" (1969) uses rapid key shifts inspired by Coltrane. Herbie Hancock employs similar cycles in "Dolphin Dance" (compressed form).

- Progressive Rock: Tool's "Lateralus" (2001) applies major-third modulations in its bridge section. King Crimson's "Red" uses chromatic mediants derived from this concept.

- Film Scoring: Composers like John Williams ("Catch Me If You Can" theme) use Coltrane-esque cycles for tension during chase sequences.

- Contemporary Jazz: Brad Mehldau's "Unrequited" (2004) reimagines the changes in odd meters. Avishai Cohen's "Pinzin Kinzin" incorporates them into Israeli folk harmonies.

Online Resources

- Jazz Advice: "Coltrane Changes Demystified" (interactive chord charts)

- OpenStudio Jazz: Peter Martin's "Giant Steps Masterclass" (video breakdowns)

- Jazz at Lincoln Center: "Coltrane's Harmonic Architectures" (lecture archive)