Summary:

Musical notation is the elegant and universal system that allows musicians to read, write, and share the language of music. It transforms abstract sounds into concrete symbols, enabling the documentation and preservation of musical ideas across centuries and cultures. This comprehensive guide delves into the core components of modern staff notation, including the staff, clefs, notes, rests, time signatures, and key signatures. Whether you are a beginner eager to decipher your first piece of sheet music or an experienced musician seeking to refine your theoretical foundation, this article provides the essential knowledge to unlock the rich world of music literacy.

Keywords:

musical notation, music theory, how to read music, staff, clefs, treble clef, bass clef, notes, rests, time signature, key signature, music reading, rhythm, note duration, grand staff, ledger lines, music symbols

Introduction:

Imagine a language that transcends spoken words, capable of conveying deep emotion, intricate patterns, and soaring melodies. This is the language of music, and musical notation is its written form. Just as written text allows us to record stories and knowledge, musical notation empowers composers to capture their creations in a tangible format, ensuring their music can be performed, studied, and enjoyed long after its conception.

For over a thousand years, this system has evolved from simple melodic contours into the precise and expressive language we use today. Learning to read music opens up a vast universe of artistic works, from the intricate fugues of Bach to the epic scores of modern film. It provides a common ground for musicians of all backgrounds to collaborate, share ideas, and bring a composer's vision to life. This guide will walk you through the fundamental building blocks of musical notation, equipping you with the skills to begin your journey toward musical fluency.

The Staff: Music's Canvas

The Five-Line Staff

The foundation of all written music is the staff (or stave), a set of five parallel horizontal lines and the four spaces between them. Each line and space represents a specific musical pitch. As notes are placed higher on the staff, they represent higher pitches; as they are placed lower, they represent lower pitches. This creates a visual grid for melody.

When a pitch is too high or low to fit on the staff, we use ledger lines—short, additional lines extending above or below the staff. These temporary lines maintain the consistent pattern of lines and spaces, allowing us to notate any pitch imaginable.

Clefs: The Key to the Map

A clef is a symbol placed at the very beginning of the staff. Its job is to assign a specific pitch to a specific line, thereby fixing the pitch of all other lines and spaces. The type of clef used depends on the range of the instrument or voice. The most common clefs are:

- Treble Clef (G-Clef): Its elegant swirl curls around the second line from the bottom, designating that line as the pitch G above Middle C. It is used for high-pitched instruments (like the flute, violin, or trumpet) and the right hand of the piano. A common mnemonic for its lines (E-G-B-D-F) is "Every Good Boy Does Fine," and for its spaces (F-A-C-E), the word "FACE."

- Bass Clef (F-Clef): Evolved from a stylized letter 'F', its two dots surround the fourth line from the bottom, designating it as the F below Middle C. It is used for low-pitched instruments (like the cello, bassoon, or tuba) and the left hand of the piano. Mnemonics for its lines (G-B-D-F-A) include "Good Boys Do Fine Always," and for its spaces (A-C-E-G), "All Cows Eat Grass."

- C-Clef: This movable clef positions Middle C on the line at its center. The Alto Clef (used by the viola) places Middle C on the middle line, while the Tenor Clef (used for the upper ranges of the cello and trombone) places it on the fourth line from the bottom.

In piano music, the treble and bass clefs are often combined into a Grand Staff, connected by a brace. This allows for the notation of a wide range of pitches, covering both hands of the pianist. Middle C sits on a ledger line precisely between the two staves.

Example: The Grand Staff and Middle C

This example shows the Grand Staff, with the Treble and Bass clefs, and the location of Middle C (C4) on a ledger line between them.

Notes and Rests: Sound and Silence

While the staff tells us a note's pitch, the design of the note itself tells us its duration—how long it should be held. The components of a note are the notehead (the oval part) , the stem (the vertical line), and the flag (the curved line attached to the stem).

Note Values

Note durations are relative to each other, forming a system of mathematical divisions. The most common values are:

- Whole note (Semibreve): An open notehead with no stem. It is the longest standard note value.

- Half note (Minim): An open notehead with a stem. Two half notes equal the duration of one whole note.

- Quarter note (Crotchet): A filled-in notehead with a stem. Two quarter notes equal one half note.

- Eighth note (Quaver): A filled-in notehead with a stem and one flag. Two eighth notes equal one quarter note.

- Sixteenth note (Semiquaver): A filled-in notehead with a stem and two flags. Two sixteenth notes equal one eighth note.

To simplify reading, consecutive eighth notes (or shorter values) are often grouped together with beams, which replace the individual flags.

Rests: The Sound of Silence

Music is not just about the sounds, but also the silences between them. For every note value, there is a corresponding rest of equal duration.

- Whole rest: A rectangle hanging from the fourth line.

- Half rest: A rectangle sitting on the third line.

- Quarter rest: A squiggly symbol.

- Eighth rest: A symbol with one flag, resembling a '7'.

- Sixteenth rest: A symbol with two flags.

Dotted Notes and Ties

A dot placed after a notehead increases its duration by half of its original value. For example, a half note is worth two beats; a dotted half note is worth three beats (2 + 1). A tie is a curved line connecting two notes of the same pitch, merging them into a single, sustained sound. Ties are often used to hold a note across a bar line.

Example: Rhythmic Division and Dotted Notes

The first measure shows the division of a whole note. The second measure shows how a dotted quarter note (equal to 1.5 quarter notes) works in practice.

Time Signatures: The Rhythmic Framework

The time signature appears after the clef and key signature. It is a fraction that organizes the music into regular groupings of beats, contained within measures (or bars) , which are separated by vertical bar lines.

- The top number tells you how many beats are in each measure.

- The bottom number tells you which note value gets one beat (4=quarter note, 2=half note, 8=eighth note).

Time signatures are categorized as Simple (where each beat divides into two) or Compound (where each beat divides into three).

- 4/4 (Common Time): Simple time. Four quarter-note beats per measure. Indicated by a large "C".

- 3/4: Simple time. Three quarter-note beats per measure (e.g., a waltz).

- 2/2 (Cut Time): Simple time. Two half-note beats per measure. Indicated by a "C" with a vertical line through it.

- 6/8: Compound time. Two beats per measure, with each beat being a dotted quarter note (which divides into three eighth notes). This creates a lilting, "two-group" feel.

Key Signatures: The Tonal Center

The key signature is a collection of sharps (#) or flats (b) placed after the clef. It establishes the "home" tonality of the piece by indicating which notes are to be played a semitone higher or lower throughout the music, unless cancelled by an accidental (a temporary sharp, flat, or natural sign).

Sharps and flats always appear in a specific order. For sharps, the order is F-C-G-D-A-E-B. For flats, it's the reverse: B-E-A-D-G-C-F. A helpful trick to identify the key: for sharp keys, the key is a half-step up from the last sharp. For flat keys, the second-to-last flat is the name of the key (except for F major with one flat).

Sharp and Flat Keys

- G major / E minor: One sharp (F#)

- D major / B minor: Two sharps (F#, C#)

- F major / D minor: One flat (Bb)

- Bb major / G minor: Two flats (Bb, Eb)

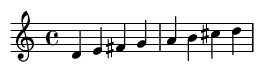

Example: D Major Scale with Key Signature

Notice how the F and C are automatically played as F-sharp and C-sharp because of the key signature, without needing individual accidentals on the notes.

Historical Development:

Today's sophisticated system of notation is the result of a long evolution. Its roots lie in 9th-century Europe with neumes, simple markings above liturgical texts that indicated the general contour of a melody but not specific pitches or rhythms. The true breakthrough came with Guido of Arezzo (c. 991–1033) , an Italian monk who standardized a four-line staff, allowing for precise pitch notation for the first time. He also developed the system of solmization (solfege) that became the foundation for how we name notes today.

Through the Renaissance and Baroque periods, notation was refined with the addition of the five-line staff, standardized note shapes for rhythm, bar lines, and key signatures. By the Classical era, composers could add detailed instructions for dynamics (loudness), articulation (how a note is attacked), and tempo (speed), making scores increasingly precise blueprints for performance. The 20th and 21st centuries have continued this evolution, with composers inventing new symbols for extended techniques, microtonal music, and electronic elements, proving that musical notation is a living, adaptable language.

Interesting Facts:

- The symbols for sharp (#) and flat (b) likely originated from different stylized versions of the letter 'b'. One was squared ('b durum' or hard b) for a higher pitch, and the other rounded ('b molle' or soft b) for a lower pitch.

- The term "staff" comes from the Old English word "stæf," meaning stick or pole, evoking the image of lines drawn across a page.

- The bass clef is also called the F-clef because it evolved from a Gothic letter 'F' and marks the position of the note F on the staff. Similarly, the treble clef is a G-clef because it evolved from a scripted 'G'.

- Before the invention of the staff, music was primarily passed down orally, making it prone to change and loss over time. Notation was a revolutionary technology for preserving musical heritage.

- While Western notation is dominant, many cultures have unique and powerful notation systems. Chinese music often uses numbered notation (jianpu), and Indonesian gamelan music uses symbolic grid-based notation.

Conclusion:

Musical notation is more than a set of rules; it is the bridge between the composer's imagination and the performer's interpretation. Learning to read music is like learning a new language—one that unlocks access to a global library of artistic expression. It empowers you to understand the structure behind the music you love, to communicate precisely with fellow musicians, and to engage with musical works on a profoundly deeper level.

While modern tools like tablature and software are useful, fluency in traditional notation is an invaluable skill that provides a complete and universal framework for musical understanding. As you continue your musical journey, be patient and persistent. Every piece of music you decode is a conversation with the past, a connection to a timeless artistic tradition, and a step toward mastering the beautiful and enduring language of music.

References:

-

Read, Gardner. "Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice." Taplinger Publishing Company, 1979.

-

Stone, Kurt. "Music Notation in the Twentieth Century: A Practical Guidebook." W. W. Norton & Company, 1980.

-

Gerou, Tom, and Lusk, Linda. "Essential Dictionary of Music Notation." Alfred Music, 1996.

-

Rastall, Richard. "The Notation of Western Music: An Introduction." St. Martin's Press, 1982.