Summary:

The Lydian mode, characterized by its distinctive raised fourth degree, creates a bright, optimistic, and often magical sound that has captivated composers and improvisers. This comprehensive guide explores the theoretical structure of the Lydian mode, its historical development from church music to modern applications, and its widespread use in jazz, film scoring, and contemporary music. Understanding this versatile mode opens new creative avenues for composition and improvisation across diverse musical genres.

Keywords:

Lydian mode, modal harmony, raised fourth, church modes, jazz theory, film music, modal jazz, film scoring techniques, modal interchange, lydian dominant, George Russell, Lydian Chromatic Concept

Introduction:

Among the seven traditional modes of Western music, the Lydian mode stands out for its uniquely bright and uplifting character. Named after the ancient kingdom of Lydia, this scale has traversed centuries of musical evolution to become one of the most versatile and expressive tonal colors in modern composition and improvisation.

What distinguishes the Lydian mode is its raised fourth degree—the characteristic "Lydian note" that creates a tritone with the tonic. This seemingly simple alteration generates a sound that can be simultaneously ethereal and open, dreamy and expectant. Unlike the major scale, whose perfect fourth can create a clashing "avoid note" over the tonic chord, the Lydian's raised fourth floats consonantly, contributing to its feeling of stability and lift. It's no wonder that film composers reach for Lydian colors to evoke wonder and mystery, while jazz musicians employ it to add sophisticated tensions to their improvisations.

In this article, we'll deconstruct the theoretical structure of the Lydian mode, trace its historical journey, and examine its practical applications across various musical contexts. Whether you're a composer seeking new harmonic colors, an improviser looking to expand your melodic vocabulary, or simply a curious music lover, the Lydian mode offers a fascinating window into the expressive potential of modal harmony.

Theoretical Structure:

Scale Formula and Construction

The Lydian mode is the fourth mode of the major scale. You can construct it by starting on the fourth degree of any major scale. For example, starting on F and playing the notes of the C Major scale (F G A B C D E) produces the F Lydian mode.

The interval structure of the Lydian mode is a series of three consecutive whole steps followed by a half step:

- Tonic to Major Second: Whole Step (W)

- Major Second to Major Third: Whole Step (W)

- Major Third to Augmented Fourth: Whole Step (W)

- Augmented Fourth to Perfect Fifth: Half Step (H)

- Perfect Fifth to Major Sixth: Whole Step (W)

- Major Sixth to Major Seventh: Whole Step (W)

- Major Seventh to Octave: Half Step (H)

This can be abbreviated as W-W-W-H-W-W-H.

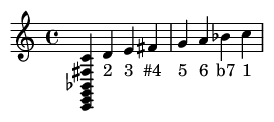

In terms of scale degrees, the Lydian mode is defined as:

- 1 (Tonic)

- 2 (Major Second)

- 3 (Major Third)

- #4 (Augmented Fourth)

- 5 (Perfect Fifth)

- 6 (Major Sixth)

- 7 (Major Seventh)

The defining characteristic is the augmented fourth (#4), which gives the mode its bright, open quality.

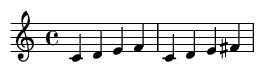

Example: C Lydian Scale

Comparison with Major Scale (Ionian Mode)

To hear the Lydian mode's unique character, compare it directly to the familiar major scale. The only difference is the fourth degree.

Example: C Major vs. C Lydian

This single note change from F-natural to F-sharp transforms the scale's character from grounded and familiar to open and magical.

Diatonic Chords in Lydian

Building seventh chords on each degree of the Lydian mode (using C Lydian: C D E F# G A B) produces a unique harmonic palette:

- Imaj7 (Cmaj7: C-E-G-B)

- II7 (D7: D-F#-A-C) - A dominant 7th chord, a major difference from the minor ii chord in a major key.

- iiim7 (Em7: E-G-B-D)

- #ivm7(b5) (F#m7b5: F#-A-C-E) - A half-diminished chord on the characteristic raised fourth.

- Vmaj7 (Gmaj7: G-B-D-F#) - A major 7th, not the dominant V7 found in a major key. This lack of a strong V-I pull contributes to the "floating" quality of Lydian harmony.

- vim7 (Am7: A-C-E-G)

- viim7 (Bm7: B-D-F#-A)

The most distinctive chords are the II7 and the Vmaj7, which fundamentally alter the harmonic landscape compared to the standard major key.

Historical Development:

Ancient and Medieval Origins

The name "Lydian" derives from Lydia, an ancient kingdom in Asia Minor. However, the ancient Greek *tonoi* were organized differently from our modern modes. The Lydian mode as we know it was codified in the Middle Ages as one of the authentic church modes, used as a melodic framework for Gregorian chant. It was designated as Mode V, with its final (tonic) on F.

Renaissance to Classical Eras

During the rise of functional tonality (the major/minor system), the Lydian mode's tritone between the tonic and the fourth degree was often considered a dissonance to be resolved or avoided. Composers sometimes flattened the fourth degree (a practice known as *musica ficta*), effectively turning the Lydian mode into the Ionian mode (our major scale).

However, some composers used its unique color for expressive purposes. A celebrated example is Ludwig van Beethoven's String Quartet No. 15, Op. 132. The third movement is titled "Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart" (Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian Mode), where he masterfully uses the mode's ethereal quality to express profound gratitude and spirituality.

The 20th Century Modal Renaissance

The 20th century saw a rediscovery of the modes. Impressionist composers like Debussy and Ravel used modal colors, while ethnomusicologists like Béla Bartók found Lydian patterns in the folk music of Eastern Europe.

A revolutionary development came with jazz theorist George Russell's "Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization" (1953). Russell argued that the Lydian scale is more acoustically consonant with a major chord than the major scale itself, because it aligns more closely with the natural overtone series. He proposed Lydian as the primary scale of tonal gravity, a concept that profoundly influenced modal jazz pioneers like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans.

Practical Applications:

The Lydian Mode in Jazz

In jazz, the Lydian mode is a go-to choice for improvising over major 7th chords (Imaj7 and IVmaj7). The #4 is not treated as an "avoid note" like the P4 of the major scale; instead, it's a colorful extension that adds a modern, bright tension.

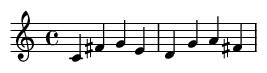

Example: Lydian Jazz Lick over Cmaj7

Many classic modal jazz compositions are built on Lydian harmony, including:

- Miles Davis's "So What" (the D Dorian sections can be re-conceptualized from a Lydian perspective)

- Herbie Hancock's "Maiden Voyage" (built on static chords often improvised over with Lydian and other modes)

- Joe Henderson's "Inner Urge"

Lydian in Film and Contemporary Music

The Lydian mode is a staple in film scoring for its ability to instantly create a sense of wonder, magic, or vast, open landscapes.

Notable examples include:

- John Williams' "Flying Theme" from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (the archetypal example)

- Alan Silvestri's main theme from Back to the Future

- Danny Elfman's theme from The Simpsons (uses Lydian Dominant for a quirky feel)

- Howard Shore's "Shire" theme from The Lord of the Rings

In pop and rock, it's used by artists seeking a more sophisticated or atmospheric sound:

- Björk ("Possibly Maybe")

- Joe Satriani ("Flying in a Blue Dream")

- Grizzly Bear ("Two Weeks")

Lydian Variants and Derivatives

The Lydian sound is so foundational that it serves as the basis for other important scales.

Lydian Dominant (Lydian b7)

This scale (1, 2, 3, #4, 5, 6, b7) is the fourth mode of the melodic minor scale. It blends the bright #4 of Lydian with the b7 of a dominant chord, making it perfect for improvising over dominant 7(#11) chords.

Example: C Lydian Dominant Scale

Lydian Augmented

This scale (1, 2, 3, #4, #5, 6, 7) is the third mode of the melodic minor scale. It features both a raised fourth and a raised fifth, creating an exceptionally bright, tense, and otherworldly sound used in modern jazz and fusion over maj7(#5) chords.

Example: C Lydian Augmented Scale

Compositional Techniques:

Modal Interchange with Lydian

A powerful technique is "modal interchange" (or "borrowing"), where chords from a parallel mode are used in a major key context. Borrowing the II7 chord from Lydian to replace the standard iim7 adds a sudden brightness and forward momentum to a progression.

Example: Modal Interchange | C: iim7-V7-I vs. II7(Lydian)-V7-I

Lydian Pedal Points

A common film scoring technique involves holding a tonic note or chord (a pedal point) in the bass while a Lydian melody floats above it. This creates a stable yet magical atmosphere, grounding the harmony while allowing the #4 to add its characteristic lift.

Practicing the Lydian Mode:

Technical Exercises

To internalize the Lydian sound, move beyond simply playing the scale up and down. Practice melodic patterns that emphasize the characteristic intervals.

- Practice the scale in all 12 keys, starting from the fourth degree of each major scale.

- Play Lydian arpeggios that include the extensions (e.g., C-E-G-B-D-F#-A).

- Practice patterns that pivot around the #4, such as (1-2-3-#4) or (#4-5-6-7).

Example: Lydian Pattern (1-#4-5-3)

This pattern forces you to hear and feel the crucial relationship between the tonic, the bright #4, the stable 5th, and the major 3rd.

Improvisation Approaches

- Target the Colors: Emphasize the #4, 6, and 7. These notes define the Lydian sound against a major tonic chord.

- Think in Triads: Superimpose major triads built on the 2nd degree (the II chord) over the tonic chord. For C Lydian, playing a D major triad (D-F#-A) over a C bass note instantly creates the Lydian sound.

- Avoid Clichés: Move beyond just running the scale. Create melodic phrases that tell a story using the Lydian palette.

Key Figures in Lydian Theory and Application:

George Russell (1923-2009)

The father of modern Lydian theory. His "Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization" presented a new way of understanding harmony based on acoustical principles, placing Lydian at the center of tonal gravity. His work is a cornerstone of modern jazz education.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

A pioneering composer and ethnomusicologist who integrated modal sounds from Eastern European folk music into his work. His compositions often feature Lydian inflections that blend folk authenticity with modernist harmony.

John Williams (b. 1932)

Arguably the composer most responsible for popularizing the Lydian sound in the cultural consciousness. His film scores for E.T., Star Wars, and Superman masterfully use Lydian harmony to signify heroism, wonder, and the sublime.

Fun Facts:

- The main theme for The Simpsons prominently features the Lydian Dominant scale, which gives it that famously quirky and slightly "off" character.

- The tritone interval (augmented fourth) between the tonic and the #4 was known in the medieval era as the *diabolus in musica* ("the devil in music"). While historically avoided in sacred music, this very interval gives Lydian its modern, magical charm.

- The Kingdom of Lydia, where the mode gets its name, was located in modern-day western Turkey and is credited with inventing the first minted coins.

- The opening octave riff of Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze," combined with the underlying harmony, creates a sound that strongly suggests Lydian, contributing to the track's psychedelic feel.

Conclusion:

The Lydian mode is far more than just a major scale with one altered note. It is a complete harmonic and melodic system that offers a distinct emotional color—one of brightness, wonder, and serene expansiveness. From its theoretical roots in church music to its central role in modern jazz and film scoring, Lydian has proven to be an enduring and powerful expressive tool.

What makes the Lydian mode so potent is its unique stability. By raising the fourth degree, it removes the only "avoid note" over a major tonic chord, creating a sound that is both consonant and yet full of tension and light. This special quality has made it invaluable for composers and improvisers seeking to express the extraordinary.

As you continue your musical journey, listen for the distinctive Lydian sound in film scores, jazz recordings, and pop music. Experiment with incorporating it into your own playing and writing. That one raised note transforms the entire character of the music—a testament to the profound power of small changes in harmony.

References:

Russell, G. (2001). The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization. Concept Publishing.

Levine, M. (1995). The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.

Persichetti, V. (1961). Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. W. W. Norton & Company.

Tymoczko, D. (2011). A Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice. Oxford University Press.

Powers, H. S., et al. "Mode." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press.