Summary:

This article explores the powerful and expressive technique of chromatic modulation. We'll demystify how composers use chromatically altered chords, enharmonic respellings, and clever voice leading to create seamless yet dramatic shifts between keys. Understanding this concept is essential for any serious musician wanting to grasp the emotional depth of music from the Romantic period to modern film scores and even jazz.

Keywords:

Chromatic Modulation, Music Theory, Harmony, Key Change, Pivot Chord, Enharmonic Modulation, Secondary Dominant, Voice Leading, Music Composition, Romantic Music, Augmented Sixth Chord

Introduction:

Have you ever listened to a piece by Schubert or Wagner and felt the musical ground suddenly shift beneath your feet? That thrilling, unexpected change in mood and color is often the work of a sophisticated technique called chromatic modulation. While simpler diatonic modulations move between closely related keys using shared chords, chromatic modulation is the composer's secret weapon for venturing into more distant and emotionally-charged tonal landscapes. It’s a journey from one key to another that takes an unexpected, yet wonderfully logical, turn by using notes outside of the established scale.

What is Chromatic Modulation? The Core Concepts

Chromatic modulation is the process of changing from one key to another using a pivot chord that is chromatic (contains notes not native) to one or both keys. It can also be achieved through a smooth chromatic melodic line that connects the keys without a traditional pivot. This creates a more surprising and intense effect than a standard diatonic modulation. The main types include:

- Modulation via an Altered Chord (e.g., Secondary Dominant): This is the most common method. A chord is chromatically altered in the original key to create a strong pull towards a new key center. For example, a secondary dominant is chromatic in the home key but functions as a powerful dominant in the new key.

- Enharmonic Modulation: A clever technique where a chord is spelled in two different ways, allowing it to function diatonically in two different and often distant keys. The re-spelling happens in the listener's mind, creating a seamless but dramatic shift. The German augmented sixth chord is famously used for this.

- Common-Tone and Linear Chromatic Modulation: This approach uses a single sustained note (a common tone) to bridge two keys, or it employs a chromatic bassline or melody to smoothly lead the listener's ear from one tonal center to another. The effect is often subtle and dreamlike.

Chromatic Modulation in Action: Musical Examples

Example 1: Modulation to the Relative Minor via a Secondary Dominant

This example shows a classic modulation from C Major to its relative minor, A minor. The pivot is the E7 chord. In C Major, this chord is V7 of vi (V7/vi), and it is chromatic because of the G#. This G# is the leading tone to A, creating an irresistible pull to establish A minor as the new tonic.

Breakdown: The progression is C: I64 - ii65 - V7/vi - a: i. The E7 chord (E-G#-B-D) functions as V7/vi in C Major, smoothly pivoting to become V7 in the new key of A minor, where it resolves to the new tonic (i).

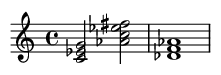

Example 2: Enharmonic Modulation (Ger+6 to V7)

Here is a classic enharmonic modulation moving from C minor to the distant key of D-flat Major. The German augmented sixth chord in C minor is spelled Ab-C-Eb-F#. This chord has a powerful tendency to resolve to the dominant (G). However, if we mentally re-spell the F# as a Gb, the chord becomes Ab-C-Eb-Gb — an Ab dominant seventh chord (Ab7). This is the V7 of Db Major, allowing for a magical shift to the new key.

Breakdown: The first chord is C minor (i) . The second is a German +6 chord in C minor (c: Ger+6). By reinterpreting F# as Gb, this becomes V7 in Db Major (Db: V7). It then resolves directly to the new tonic, Db Major (Db: I). This shift is incredibly smooth because only one note (F# to Gb) is notionally changed, yet the harmonic function is completely transformed.

Example 3: Common-Tone Modulation

In this technique, a single note is sustained from the final chord of the old key and becomes a member of the first chord in the new key. This shared note acts as an anchor, providing a smooth, almost dreamlike transition between what can be very unrelated keys. Here, we modulate from C Major to the remote key of A-flat Major by holding the note 'C' common to both tonic chords.

Breakdown: The music begins on a C Major chord (C: I) . The note C is sustained while the harmony underneath shifts to an Ab Major chord (Ab: I). The sustained C, which was the root of the first chord, becomes the third of the new chord. This common tone acts as a cognitive bridge, making the distant modulation feel gentle and logical.

Practical Applications and Historical Context:

Chromatic modulation is a cornerstone of dramatic musical storytelling. In opera and lieder, it's used to reflect a sudden change in a character's thoughts or the emotional subtext of lyrics. Franz Schubert was a master, using sudden shifts to distant keys to create profound emotional depth. Later, Richard Wagner took chromaticism to its extreme. In works like *Tristan und Isolde*, he used a web of continuous, unresolved chromatic modulations to create a sense of endless longing, pushing the boundaries of tonality.

But it's not just a classical device. Chromatic modulation is rampant in jazz, where reharmonization and substitution (like the tritone substitution, which is functionally similar to a Ger+6 modulation) are common practice. Modern film composers like John Williams and Hans Zimmer use chromatic shifts to heighten drama, create wonder, and guide the audience's emotional journey.

Fun Facts: The Chromatic Toolbox

- The famous "Tristan chord" from Wagner's opera is perhaps the most debated chord in music history. It's an intensely chromatic and ambiguous chord (F, B, D#, G#) that defies simple functional analysis and doesn't truly resolve for hours, perfectly capturing the opera's theme of unfulfilled desire.

- Augmented sixth chords come in three main "nationalities": Italian (three notes, e.g., Ab-C-F#), French (four notes, e.g., Ab-C-D-F#), and German (four notes, Ab-C-Eb-F#). The "German" version is unique because its spelling is just one note away from a dominant seventh chord, making it the perfect vehicle for enharmonic modulation.

Conclusion:

Chromatic modulation is far more than a dry music theory topic; it's a gateway to understanding how composers manipulate our emotions. It’s the art of the unexpected journey, a tool that can inject surprise, drama, and profound beauty into a piece of music. By learning to recognize these artful shifts, you deepen your appreciation for the craft of composition and the expressive power of harmony. The next time you listen to your favorite music, ask yourself: did the key ever change? And if so, how did the composer get me here?

References:

Kostka, S., Payne, D., & Almén, B. (2022). Tonal Harmony (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Rosen, C. (1998). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. W. W. Norton & Company.

Aldwell, E., & Schachter, C. (2018). Harmony & Voice Leading (5th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Historical Context and Musical Significance

Chromatic modulation emerged as a revolutionary harmonic technique during the Romantic era (c. 1820-1900), fundamentally transforming emotional expression in Western art music. Composers like Wagner, Chopin, and Liszt employed chromatic shifts to convey psychological depth and dramatic narrative in their works, most notably in Wagner's "Tristan und Isolde" where chromaticism dissolves traditional tonality. This technique allowed composers to:

- Create heightened emotional tension and resolution

- Blur tonal centers for dreamlike or ambiguous effects

- Facilitate remote key relationships previously considered jarring

- Serve as precursor to 20th-century atonality and jazz harmony

The significance lies in its ability to make distant key changes feel organic rather than abrupt, enabling composers to mirror complex human emotions through harmonic instability and resolution.

Progressive Exercises

Beginner

Practice modulating between closely related keys using secondary dominants. In C major, introduce a D7 chord (V7/V) resolving to G major. Write four-measure phrases modulating from C to G via this progression: I - V7/V - V - I (in new key). Focus on smooth voice leading with no augmented intervals.

Intermediate

Experiment with augmented sixth chords. From C major, build a German sixth chord (Ab-C-Eb-F#) functioning as pivot to D major (respelled as dominant seventh: Ab-C-Eb-Gb). Compose progressions like: C: I - Ger⁶ → D: V7 - I. Analyze Schubert's "Gretchen am Spinnrade" (D. 118) for practical examples.

Advanced

Create enharmonic modulations using diminished seventh chords. Take C°7 (C-Eb-Gb-Bbb) and reinterpret it as E°7 (E-G-Bb-Db) to pivot to F minor. Compose a sequence through three remote keys (e.g., C major → F# minor → A major) using diminished chords as pivots. Study Chopin's Prelude Op. 28 No. 14 for implementation.

Ear Training Tips

Develop recognition of chromatic modulations through targeted listening:

- Pivot Identification: Listen for chords that sound "pulled" in two directions (e.g., Tristan Chord)

- Common-Tone Drills: Isolate sustained notes during key changes (e.g., G# in A major becoming Ab in Eb major)

- Bass Line Mapping: Follow descending chromatic bass lines common in modulations (e.g., C-B-Bb-A in Neapolitan pivots)

Use apps like "Functional Ear Trainer" focusing on chromatic alterations. Transcribe modulation passages from Tchaikovsky's "Romeo and Juliet" Overture, noting where the harmonic center shifts unexpectedly.

Common Usage in Different Genres

While rooted in Romantic classical music, chromatic modulation permeates diverse genres:

- Jazz: Coltrane's "Giant Steps" employs chromatic mediants; Bill Evans uses augmented sixth chords as tritone substitutes

- Musical Theater: Sondheim's "Send in the Clowns" features enharmonic shifts between A minor and Db major

- Film Scores: John Williams' "Hedwig's Theme" (Harry Potter) uses chromatic mediants for magical quality

- Progressive Rock: Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" modulates from Bb to A via chromatic descent

In jazz and pop, these techniques often appear as "key changes by a semitone" for dramatic climaxes, though sophisticated artists use pivot chords for seamless transitions.

Online Resources

- MusicTheory.net: Chromatic Chord Modulations exercises

- YouTube: David Bennett Piano's "The Chord That Broke Classical Music"

- OpenMusicTheory: Chromatic Modulation chapter with audio examples