Summary:

The chromatic scale is the complete set of twelve pitches used in Western music, with each note separated by a semitone. This comprehensive guide explores the scale's structure, history, and notation, and demonstrates its practical application in harmony, melody, and improvisation across all genres. Mastering the chromatic scale is essential for any musician seeking a deep understanding of music theory and technique.

Keywords:

Chromatic scale, semitones, twelve-tone system, equal temperament, enharmonic equivalents, music theory, chromaticism, harmony, melody, music education.

Introduction: What is the Chromatic Scale?

In the vast world of Western music, nearly every melody, harmony, and chord is built from a simple collection of twelve fundamental pitches. This collection, when arranged in sequence, is known as the chromatic scale. Think of these twelve notes as the alphabet of music; just as letters combine to form words and sentences, these pitches combine to form the rich, expressive tapestry of musical language. From the intricate counterpoint of Bach to the searing guitar solos of rock, the chromatic scale is the essential resource that composers and performers draw upon.

The modern form of the chromatic scale was standardized with the widespread adoption of equal temperament, a tuning system that solidified in the 18th century. This system divides the octave into twelve precisely equal semitones (or half-steps), allowing music to be composed and performed in any key with consistent intonation. Understanding this scale is the first step toward unlocking the secrets of music theory, from chord construction to complex modulation.

Structure and Properties

The chromatic scale is unique because it has no tonal center; it is simply a sequence of all twelve pitches within an octave. Each pitch is separated by a semitone (or half-step), the smallest interval in traditional Western music.

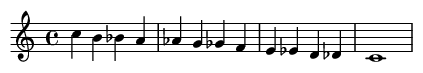

By convention, we use sharps (#) when writing the scale ascending and flats (b) when descending. This practice helps maintain clarity in notation by generally using each letter name (A, B, C, etc.) once per octave.

An ascending chromatic scale starting on C:

A descending chromatic scale starting on C:

Notation and Terminology

The twelve pitches of the chromatic scale can be described in several ways:

- Letter Name with Accidental: C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab, A, A#/Bb, B.

- Scale Degree (relative to a major scale) : 1, #1/b2, 2, #2/b3, 3, 4, #4/b5, 5, #5/b6, 6, #6/b7, 7.

- Integer Notation (in set theory): 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 (often with C as 0).

- Frequency Ratios: In equal temperament, each ascending semitone increases the pitch's frequency by a factor of the 12th root of 2 (approximately 1.05946).

Notes with the same pitch but different names (like F# and Gb) are called enharmonic equivalents. While they sound identical on a modern piano, their spelling is crucial for conveying the correct harmonic function within a piece of music.

The Chromatic Scale on Different Instruments

How musicians produce the chromatic scale varies by instrument:

- Piano: Playing the scale involves moving sequentially across all white and black keys without skipping any. The pattern is visually and physically direct.

- Guitar: Playing chromatically on one string means moving up or down one fret at a time, as each fret represents a semitone.

- Violin/Cello: Players use precise finger placements along the fingerboard, often requiring shifts in hand position to play an extended chromatic scale.

- Wind instruments: Each note requires a unique fingering or slide position, making chromatic passages a test of technical dexterity.

- Voice: Singers rely on exceptional ear training and vocal control to accurately produce the small interval of a semitone.

It's important to remember that equal temperament is a brilliant mathematical compromise. It allows musicians to play in all twelve keys without re-tuning, making complex harmonic journeys possible. In exchange, it slightly detunes most intervals compared to their "pure" ratios (just intonation), a trade-off that has defined the sound of Western music for centuries.

Historical Development

The full chromatic scale was not always the norm. Its acceptance was a gradual process:

- Ancient and Medieval Eras: Music was primarily diatonic (based on seven-note scales), with chromatic notes used sparingly as alterations.

- Renaissance: Composers like Carlo Gesualdo began using chromaticism more boldly for text painting and intense emotional expression. -

- Baroque Era: The development of well-tempered tuning systems allowed composers like J.S. Bach to explore all 24 major and minor keys in works such as "The Well-Tempered Clavier."

- Classical and Romantic Eras: Chromaticism became a key tool for modulation and adding emotional depth. Late-Romantic composers like Richard Wagner, with his famous "Tristan Chord," pushed chromatic harmony to its limits.

- 20th Century: The intense use of chromaticism led to the breakdown of traditional tonality. Arnold Schoenberg developed the twelve-tone technique, a method that organized all twelve chromatic pitches in a fixed order (a "tone row") to create atonal music.

Chromaticism in Action: Musical Techniques

Musicians use chromatic notes to add color, tension, and sophistication. Here are some common techniques:

Chromatic Passing and Neighbor Tones: These are non-chord tones that connect or embellish the primary notes of a melody or chord. A passing tone fills the space between two notes a whole step apart, while a neighbor tone moves a semitone away from a note and returns.

Example: A melodic phrase with a chromatic passing tone (C#) and a lower neighbor tone (F#).

Chromatic Harmony: Chromatic notes can be used to create chords that are outside the primary key, generating powerful tension and release. A classic example is the Augmented Sixth Chord, which uses chromatic alterations to pull strongly towards the dominant chord, often before a final cadence.

Example: A German Augmented Sixth chord (Ger+6) in C minor resolving to the dominant (V) and tonic (i).

The Chromatic Scale in Various Genres

Chromaticism is everywhere, though its application differs by style:

- Classical: Used for everything from subtle emotional coloring in Mozart to the structural basis of Wagner's operas.

- Jazz: Bebop musicians masterfully weave chromatic lines into their improvisations to create fluid, complex melodies. Chromatic approach notes are essential for targeting chord tones with sophistication.

- Blues: The iconic "blue notes" are a form of microtonal chromaticism, falling between the standard pitches of the scale to create a soulful, bending sound.

- Rock and Metal: Fast, aggressive chromatic riffs are a hallmark of many metal subgenres, providing a sense of power and dissonance.

- Film Music: Composers use chromaticism to build suspense, express anguish, or create magical atmospheres. The jarring string stabs in Bernard Herrmann's score for *Psycho* are a famous example.

Example: A classic Bebop phrase over a ii-V-I progression in C Major. Notice the chromatic line (Bb-A-Ab-G) smoothly connecting the Dm7 and G7 chords.

Practical Applications for Musicians

Integrating the chromatic scale into your practice routine is transformative:

- Technical Facility: Practicing chromatic scales builds finger dexterity, speed, and precision on any instrument.

- Ear Training: Singing and identifying chromatic intervals sharpens your pitch perception and ability to recognize complex melodies.

- Improvisation: The chromatic scale provides a universal toolkit for connecting ideas and moving seamlessly between different tonal centers.

- Composition and Analysis: Understanding chromaticism allows you to create more expressive music and to deconstruct the techniques used by the great composers.

A fundamental technical exercise: Practice ascending and descending in four-note groups to build evenness and control.

Conclusion

The chromatic scale is far more than a simple technical exercise; it is the elemental source of pitch material in Western music. Its historical development from a rare expressive device to a structural foundation mirrors the evolution of musical language itself. By providing all twelve semitones, it empowers musicians to create tension and release, to move between keys with grace, and to add infinite shades of emotional color to their work.

Developing fluency with the chromatic scale—intellectually, aurally, and physically—is a rite of passage for every serious musician. It bridges the gap between theory and practice, opening up a world of creative possibilities. From its simplest form to its most complex harmonic applications, the chromatic scale remains the versatile and indispensable alphabet of our musical expression.

References:

-

Kostka, S., & Payne, D. (2018) . Tonal Harmony: With an Introduction to Post-Tonal Music (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

-

Persichetti, V. (1961). Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. W. W. Norton & Company.

-

Schoenberg, A. (1983). Theory of Harmony (R. E. Carter, Trans.). University of California Press. (Original work published 1911)

-

Isacoff, S. (2003). Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization. Vintage.

-

Levine, M. (1995). The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.