Summary:

The blues scale is a fundamental musical tool that captures the expressive, soulful heart of the blues and has profoundly influenced countless genres, from jazz and soul to rock and beyond. This article delves into the scale's unique structure, its historical origins, and its sonic character. Through clear explanations, practical musical examples for various instruments, and targeted exercises, you will learn how this simple six-note scale became the foundation for much of the world's most popular music.

Keywords:

blues scale, blue notes, minor pentatonic, improvisation, music theory, blues music, jazz, rock, guitar soloing, musical expression, piano blues

Introduction: What is the Blues Scale?

Few musical concepts have shaped modern music as powerfully as the blues scale. Born from the African-American experience in the American South during the late 19th century, this scale is more than a sequence of notes; it’s a vessel of emotion. It masterfully fuses West African melodic sensibilities with European harmonic structures, creating a sound that is unique, versatile, and deeply human.

The magic of the blues scale lies in its ability to convey an incredible range of feeling. From the deepest sorrow to the most uninhibited joy, it provides a universal language for musicians to share their stories. Its defining feature is a built-in tension, a "cry" that gives melodies their distinctive, soulful quality.

Technically, the standard blues scale is a hexatonic (six-note) scale. It's built from a familiar framework—the minor pentatonic scale—but with one crucial addition: a chromatic passing tone known as the "blue note." This single added note unlocks a world of expressive possibilities that have become the melodic bedrock of blues, jazz, rock, soul, and countless other popular music genres.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore the structure of the blues scale, its historical journey, and its practical application on different instruments. With exercises and examples to guide you, you'll be ready to integrate this essential sound into your own musical vocabulary, whether you're a complete beginner or a seasoned musician.

The Structure of the Blues Scale

The Six Notes of the Blues

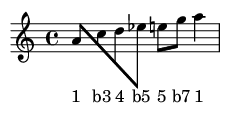

The standard (or minor) blues scale is built using the following scale formula:

Root (1) - Minor Third (b3) - Perfect Fourth (4) - Diminished Fifth (b5) - Perfect Fifth (5) - Minor Seventh (b7)

The Diminished Fifth (b5) is the famous "blue note" that gives the scale its name and characteristic sound. For example, let's build the A Blues Scale:

- 1 (Root): A

- b3 (Minor Third): C

- 4 (Perfect Fourth): D

- b5 (Blue Note): Eb

- 5 (Perfect Fifth): E

- b7 (Minor Seventh): G

So, the A Blues Scale consists of the notes: A - C - D - Eb - E - G.

Relationship with the Pentatonic Scale

The blues scale is a direct descendant of the minor pentatonic scale. The only difference is the added b5 "blue note."

A Minor Pentatonic Scale: A - C - D - E - G (1 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b7)

A Blues Scale: A - C - D - Eb - E - G (1 - b3 - 4 - b5 - 5 - b7)

This added note creates a chromatic passing tone between the 4th and 5th degrees, introducing the dissonance and tension that is central to the blues sound.

The "Blue Note" and its Significance

While the b5 is the most famous "blue note," the term can also refer to the minor third (b3) and minor seventh (b7), especially when they are played against major chords in a blues progression. This creates a powerful clash between minor and major tonalities.

The true soul of the blue note isn't just its pitch, but how it's played. On instruments that allow for pitch bending (like guitar, harmonica, or the human voice), the blue note is often treated as a fluid, expressive target. A guitarist might bend the 4th degree (D) up *towards* the b5 (Eb), never quite landing on a fixed pitch. This microtonal "smear" is a direct attempt to replicate the nuances of the human voice, capturing the pain, longing, and release that defines the blues.

Origin and History of the Blues Scale

African Roots and Cultural Fusion

The origins of the blues scale are intertwined with the history of enslaved Africans in the United States. Many West African musical traditions utilized pentatonic (five-note) scales and featured a fluid, speech-like approach to melody that didn't conform to the rigid tuning of European classical music. When these traditions met the hymns and harmonies of European culture, a new musical language began to form.

The "blue notes" can be understood as an attempt by early African-American musicians to find those "in-between" microtonal pitches from their own traditions on Western instruments. The work songs, field hollers, and spirituals of the 19th century were the crucible where this new sound was forged.

From the Field to the Stage

As blues evolved from a rural folk tradition into a more structured musical form, so too did its melodic and harmonic conventions. The 12-bar blues progression became a standard framework. Composers like W.C. Handy, often called "The Father of the Blues," were pivotal in codifying and popularizing the blues in the early 20th century, arranging folk melodies for bands and publishing sheet music that brought the sound to a wider audience.

During the Great Migration, millions of African Americans moved from the rural South to industrial cities in the North. They brought the blues with them, and in cities like Chicago and Memphis, the music electrified and evolved, influencing and being influenced by other nascent genres like jazz.

From Blues to Jazz, Rock, and Beyond

The blues scale and its underlying feel became a cornerstone of jazz. Early jazz pioneers like Louis Armstrong used blues phrasing in their improvisations. Later, bebop masters like Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk applied the scale's raw expression to increasingly complex harmonic landscapes.

In the 1950s, rhythm and blues artists supercharged the blues, paving the way for rock and roll. Figures like Chuck Berry built an entire guitar style around blues licks. By the 1960s, blues-rock titans like Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, and Jimmy Page had made the blues scale the definitive language of the lead guitar, a status it still holds today.

The Blues Scale on Different Instruments

Guitar

The guitar is arguably the instrument most associated with the modern blues scale. Its ability to bend strings allows players to perfectly emulate the vocal cry of the blue notes. The most common starting point for learning the scale is the first "box" pattern. For the A blues scale, this is found at the 5th fret:

e|-----------5---8-| (Notes: A, C) B|-----------5---8-| (Notes: E, G) G|-----------5---7-| (Notes: C, D) D|-----------5---7-| (Notes: G, A) A|-------5-6-7-----| (Notes: D, Eb, E) E|-----------5---8-| (Notes: A, C)

Notice this is the standard A minor pentatonic box pattern, with the added blue note (Eb) on the 6th fret of the A string. Common guitar techniques to bring the scale to life include:

- Bends: Bending a string to raise its pitch, often targeting a note in the scale (e.g., bending from D up to E, or from G up to A).

- Vibrato: A rapid, subtle oscillation of a note's pitch for sustain and expression.

- Slides: Sliding smoothly from one note to another on the same string.

- Hammer-ons and Pull-offs: Legato techniques for fluidly connecting notes without picking every one.

Piano and Keyboards

While a piano cannot bend notes, blues pianists developed a rich vocabulary of techniques to convey a bluesy feel. The percussive nature of the instrument gives the scale a punchy, rhythmic quality. For the A blues scale, the notes are simply A-C-D-Eb-E-G.

Pianists simulate the "bending" effect using techniques like:

- Grace Notes: Quickly playing a neighboring note (often a black key) just before a main note to create a "crushed" sound. For example, quickly playing C# before landing on D.

- Trills and Tremolos: Rapidly alternating between two notes to create tension and shimmer.

- Crushing Notes: Playing adjacent notes like the b3 and 3 (C and C# in the key of A) together to create a dissonant "cluster" that resolves.

Harmonica

The diatonic harmonica is an iconic blues instrument precisely because of its ability to bend notes. The most common way to play blues is called "cross harp" or 2nd Position. This means using a harmonica keyed in a different key than the song. For example, to play blues in the key of G, a player would use a C harmonica.

Using a C harmonica in 2nd Position (Key of G), a player can access the G blues scale (G-Bb-C-Db-D-F) through a combination of drawing, blowing, and bending notes. This technique is what gives blues harp its signature wailing sound.

Voice

The voice was the original blues instrument, and it remains the most expressive. Blues singers intuitively manipulate pitch and timbre to convey emotion, using the notes of the blues scale as a guide rather than a rigid rule.

- Melisma: Singing multiple notes over a single syllable of a lyric.

- Scoops and Slides: Approaching a target note by sliding up or down into it.

- Growls and Grit: Adding a rough, distorted texture to the voice for emotional emphasis.

Singers from Bessie Smith and Robert Johnson to B.B. King and Howlin' Wolf are masters of using these techniques to tell a story with the blues scale.

How to Use the Blues Scale

Over a 12-Bar Blues Progression

The most common context for the blues scale is the 12-bar blues progression. In the key of A, a standard progression uses three chords: A7, D7, and E7.

| A7 | A7 | A7 | A7 |

| D7 | D7 | A7 | A7 |

| E7 | D7 | A7 | E7 |

Here’s the brilliant part: you can use the A blues scale to improvise over the entire progression. When you play the A blues scale over the D7 and E7 chords, its notes create unique harmonic colors and tensions. For example, playing the b3 of the A blues scale (C) over the D7 chord creates a cool, jazzy sound (it's the minor 7th of D7). Playing the b5 (Eb) over the E7 chord creates a sharp, dissonant tension (the b9 of E7) that begs to be resolved.

Example: A Simple Blues Lick over an A7 Chord

In Jazz

Jazz musicians use the blues scale to inject a "down-home" or "earthy" feel into harmonically complex situations. They often:

- Weave it with other scales: An improviser might play a bebop scale over a chord and then switch to the blues scale for a contrasting, soulful phrase.

- Apply it to different chords: Playing a G blues scale over a Cmaj7 chord can create interesting tensions and a modern sound.

- Use it in "modal" contexts: In tunes that stay on one chord for a long time, the blues scale is a perfect tool for creating melodic interest.

In Rock

Rock music took the blues scale and amplified it. In rock, the scale is often used to create:

- Iconic Riffs: Many of the greatest guitar riffs (think "Smoke on the Water" or "Back in Black") are built from the notes of the blues scale.

- Aggressive Solos: Rock guitarists often use distortion, high speed, and dramatic string bends to deliver blues scale licks with power and attitude.

- Powerful Melodies: The scale's inherent catchiness makes it perfect for vocal melodies and hooks.

Example: Classic Rock Riff using A Blues Scale

Exercises to Master the Blues Scale

Exercise 1: Basic Familiarization

Play the scale up and down in several different keys. Start slowly and focus on clean execution. Listen carefully to the sound of the b5 as you pass through it. Say the scale degrees (1, b3, 4, etc.) as you play to internalize the structure.

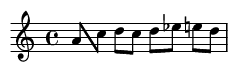

Exercise 2: Sequential Patterns

Practice playing the scale in sequences to build fluency and break away from just running up and down. Try playing in groups of three, for example: (A-C-D), (C-D-Eb), (D-Eb-E), etc.

Exercise: A 3-Note Sequence in A Blues

Exercise 3: Improvising with a Backing Track

Find a "12-bar blues in A" backing track on YouTube or a music app. Start by improvising using only 2 or 3 notes of the scale (e.g., A, C, and D) . Focus on rhythm and phrasing. Don't try to play a lot of notes; try to make a simple idea sound good. Gradually add more notes from the scale as you become more comfortable. Remember that the space *between* the notes is as important as the notes themselves!

Variations and Extensions

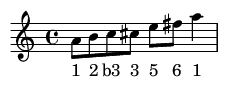

Major Blues Scale

While less common, there is a "major" version of the blues scale. It's often used in country and more upbeat blues styles. It has a brighter, happier sound, but with a touch of bluesy flavor from the b3.

Formula: 1 - 2 - b3 - 3 - 5 - 6

In the key of A, this would be: A - B - C - C# - E - F#. Here, the C natural acts as the "blue note" against the major tonality.

Combining Minor and Major Blues

Advanced players don't choose one scale or the other; they seamlessly blend them. A common technique is to use the minor blues scale over the I and IV chords (A7 and D7) and then switch to the major blues scale over the V chord (E7) for a brighter, more "resolving" sound before returning to the root. This mixing of major and minor sounds is the secret to a sophisticated blues vocabulary.

Classic Blues Licks

"Licks" are short, memorable melodic phrases that form the building blocks of a solo. Here are a few classic licks using the A blues scale that you can learn and adapt.

Lick 1: The Classic Bend

This lick uses a bend from the 4th (D) up to the 5th (E), creating a classic vocal-like cry.

Lick 2: The Turnaround

A "turnaround" is a phrase played in the last two bars of a blues progression to lead back to the beginning. This one descends through the scale to land firmly on the root.

Conclusion: More Than Just Notes

The blues scale is one of the most important musical innovations of the 20th century. With its characteristic "blue note" and deep emotional range, it provided the raw material for entire genres and continues to influence popular music across the globe.

What makes the blues scale timeless is its ability to communicate what words cannot. It’s a direct line to feeling, a way to express everything from despair to celebration. By learning its structure and, more importantly, its feel, you are not just acquiring a technical tool for improvisation. You are connecting with a deep and powerful current of musical history that is still as vital today as it was in the juke joints and on the back porches of the American South over a century ago.

References:

-

Palmer, Robert. (1982) . "Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta". Penguin Books.

-

Davis, Francis. (2003). "The History of the Blues: The Roots, the Music, the People". Da Capo Press.

-

Levine, Mark. (1995). "The Jazz Theory Book". Sher Music Co.

-

Greenblatt, Dan. (2011). "The Blues Scales: Essential Tools for Jazz Improvisation". Sher Music Co.

Historical Context and Musical Significance

Emerging from African American communities in the Deep South during the late 19th century, the blues scale evolved from spirituals, work songs, and field hollers. Its distinctive "blue notes" (flattened 3rd, 5th, and 7th scale degrees) directly reflect West African tonal systems adapted through the trauma of slavery. Early pioneers like W.C. Handy formalized these microtonal pitches into the now-standard six-note structure (1-b3-4-b5-5-b7). This scale became the emotional core of Delta blues legends like Robert Johnson, whose vocal-like guitar phrasing demonstrated its capacity for conveying raw human experience. By bending pitches and exploiting tension between major/minor thirds, musicians created the characteristic "cry" that defines blues expression, later becoming foundational to jazz improvisation through artists like Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong.

Progressive Exercises

Beginner

Practice the A blues scale (A-C-D-Eb-E-G) ascending/descending with quarter notes. Use alternate picking (guitar) or staccato articulation (piano). Improvise over a 12-bar blues loop using only rhythm variations on a single pitch.

Intermediate

Create call-and-response phrases between scale positions. Over a Bb blues backing track, target blue notes (Eb, Gb) on beat 1. Apply characteristic techniques: guitar bends (minor 3rd→major 3rd), piano grace notes, or saxophone falls.

Advanced

Transcribe B.B. King's "The Thrill Is Gone" solo. Analyze his approach to tension/release using b5 passing tones. Improvise over rhythm changes (e.g., Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time") while superimposing blues scales over ii-V-I progressions.

Ear Training Tips

Develop blue note recognition through targeted listening: Identify the b3 and b7 in Muddy Waters' "Hoochie Coochie Man" riff. Practice singing the scale against a drone note to internalize intervallic relationships. Use apps like ToneGym for microtonal bending accuracy drills. Transcribe classic blues solos by ear starting with simple phrases (e.g., Eric Clapton's "Sunshine of Your Love" intro). For chord-scale integration, play dominant 7th chords while singing blue notes over them, noticing how b5 creates dissonance against the major 3rd. Daily 5-minute sessions focusing on the minor 3rd→major 3rd bend will sharpen pitch nuance perception.

Common Usage in Different Genres

Jazz: Miles Davis' "Freddie Freeloader" uses blues scale runs over extended harmonies. Saxophonists like Sonny Rollins employ it for bebop lines with added chromaticism.

Rock: Jimmy Page's "Whole Lotta Love" solo combines E blues scale with power chords. Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Pride and Joy" demonstrates Texas shuffle applications.

Funk: Parliament-Funkadelic basslines (e.g., "Flash Light") derive from blues pentatonics with syncopated rhythms.

Soul: Aretha Franklin's vocal ad-libs in "Chain of Fools" emphasize blue notes for emotional climaxes.

Country: Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" features steel guitar blue note bends between verses.

Online Resources

- Jazz at Lincoln Center's Blues Scale Masterclass (YouTube)

- TrueFire's 30 Days to Better Blues Guitar course

- Teoria.com Interactive Scale Ear Trainer