Summary:

The major scale is one of the most fundamental pillars of Western music, providing the essential framework for melody, harmony, and composition across centuries. This article explores the structure of the major scale, its historical context, practical applications in various musical genres, and techniques for mastering it on any instrument. Through clear explanations, practical exercises, and musical examples, you will discover how this simple sequence of seven notes has shaped the sound of music from Bach to The Beatles and beyond.

Keywords:

major scale, diatonic scales, music theory, key signatures, intervals, tonality, harmony, melodic composition, Western music, circle of fifths

Introduction:

At the heart of nearly all music you know and love lies a deceptively simple pattern of notes: the major scale. This foundational sequence has shaped how we create, understand, and feel music for centuries. From the first nursery rhymes we learn to the most complex symphonies, the major scale provides the tonal "home base" upon which our musical world is built.

But what makes the major scale so special? Its unique, mathematically balanced structure creates a natural sense of stability and resolution that our ears find pleasing. Its seven notes offer just enough variety to build intricate melodies and rich harmonies. As a result, the major scale has become the benchmark from which we understand music theory, harmony, and composition in the Western tradition.

In this comprehensive guide, we will deconstruct the major scale. We'll explore its internal structure, its historical journey, its harmonic power, and its role across different musical styles. You will learn not just how to build and play major scales, but how to hear them, understand their function, and use them to unlock your own musical potential as a performer, composer, or improviser.

Whether you are a beginner taking your first steps or an experienced musician seeking to solidify your theoretical knowledge, this exploration of the major scale will provide you with invaluable tools to expand your musical vocabulary and deepen your appreciation for the music you love.

Anatomy of the Major Scale

The W-W-H-W-W-W-H Formula

The major scale is defined by a specific, unchangeable pattern of whole steps (W) and half steps (H). A half step is the smallest interval in Western music (e.g., from one piano key to the very next), and a whole step is equal to two half steps.

The formula is: Whole - Whole - Half - Whole - Whole - Whole - Half.

Starting on any note and applying this formula will produce a major scale. Let's build the most common example, the C major scale:

- C + Whole Step = D

- D + Whole Step = E

- E + Half Step = F

- F + Whole Step = G

- G + Whole Step = A

- A + Whole Step = B

- B + Half Step = C (the octave)

This specific arrangement of intervals creates a sound that our ears perceive as bright, stable, and complete, which is why it forms the basis of so many happy or triumphant-sounding songs. On a piano, the C major scale is played on all the white keys from one C to the next.

The Seven Degrees of the Scale

Each note in the major scale is called a "degree," numbered 1 through 7. Each degree has a traditional name that describes its function within the key.

- 1st degree (I) : Tonic - The "home" note. It provides a sense of arrival and resolution.

- 2nd degree (II): Supertonic - Sits one whole step above the tonic.

- 3rd degree (III): Mediant - Midway between tonic and dominant. Its interval from the tonic (a major third) defines the scale's "major" quality.

- 4th degree (IV): Subdominant - The fifth note *down* from the tonic. Creates a moderate pull away from the tonic.

- 5th degree (V): Dominant - The second most important note. It creates strong tension and a powerful desire to resolve back to the tonic.

- 6th degree (VI): Submediant - Midway between tonic and subdominant. It is also the tonic of the relative minor key.

- 7th degree (VII): Leading Tone - Just a half-step below the tonic, it creates a powerful sense of anticipation, "leading" the ear to expect a return home.

Understanding these functions is the key to unlocking how melody and harmony work together in tonal music.

Diatonic Triads: The Harmony of the Major Scale

By stacking notes in thirds on each degree of the major scale, we create a family of seven diatonic chords (triads). We use a system of Roman numerals to label these chords: uppercase for major, lowercase for minor, and a small circle for diminished.

- I: Major Chord (e.g., C-E-G in C Major)

- ii: minor Chord (e.g., D-F-A in C Major)

- iii: minor Chord (e.g., E-G-B in C Major)

- IV: Major Chord (e.g., F-A-C in C Major)

- V: Major Chord (e.g., G-B-D in C Major)

- vi: minor Chord (e.g., A-C-E in C Major)

- vii°: diminished Chord (e.g., B-D-F in C Major)

This pattern of chord qualities (Major-minor-minor-Major-Major-minor-diminished) is the same for every major key and forms the primary building blocks for harmony in countless songs.

The 15 Major Scales and Key Signatures

In Western music practice, we use a total of 15 major key signatures. This includes the 'natural' C major scale (no sharps or flats) , seven scales that use sharps (#), and seven that use flats (b). To avoid using too many accidentals in the music, we place them at the beginning of the staff in what is called a key signature.

Major Scales with Sharps

Following the circle of fifths, each new key adds one sharp. The order of sharps is always F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#.

- C major: 0 sharps/flats

- G major: 1 sharp (F#)

- D major: 2 sharps (F#, C#)

- A major: 3 sharps (F#, C#, G#)

- E major: 4 sharps (F#, C#, G#, D#)

- B major: 5 sharps (F#, C#, G#, D#, A#)

- F# major: 6 sharps (F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#)

- C# major: 7 sharps (F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#)

Major Scales with Flats

Moving in the other direction around the circle of fifths, each new key adds one flat. The order of flats is the reverse of sharps: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb.

- F major: 1 flat (Bb)

- Bb major: 2 flats (Bb, Eb)

- Eb major: 3 flats (Bb, Eb, Ab)

- Ab major: 4 flats (Bb, Eb, Ab, Db)

- Db major: 5 flats (Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb)

- Gb major: 6 flats (Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb)

- Cb major: 7 flats (Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb)

Enharmonic Scales

While there are 15 written key signatures, some are *enharmonic*—they sound identical on an instrument like the piano but are spelled differently. This means there are only 12 unique-sounding major scales. The three enharmonic pairs are:

- B major (5 sharps) and Cb major (7 flats)

- F# major (6 sharps) and Gb major (6 flats)

- C# major (7 sharps) and Db major (5 flats)

The choice between them usually depends on the instrument or the musical context to make the score easier to read.

The Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is a visual diagram that elegantly shows the relationship between all 12 unique keys. Imagine a clock face with C major (no sharps/flats) at the 12 o'clock position.

- Moving clockwise: Each step is a perfect fifth up from the previous key (C → G → D...). For each step, you add one sharp to the key signature.

- Moving counter-clockwise: Each step is a perfect fourth up (or a fifth down) from the previous key (C → F → Bb...). For each step, you add one flat to the key signature.

The circle eventually closes on itself through enharmonic keys (e.g., F# and Gb are at the 6 o'clock position). It is an invaluable tool for:

- Memorizing key signatures.

- Understanding relationships between keys.

- Composing and analyzing chord progressions (many progressions follow the circle's movement).

- Planning modulations (key changes) within a piece.

History and Evolution of the Major Scale

Ancient Origins

The roots of the major scale trace back to ancient Greece, where mathematician Pythagoras explored the consonant relationships between notes. The Greeks used various modes, and the Ionian mode had the same interval structure as our modern major scale. However, it was just one of several equally important modes.

The Middle Ages and the Renaissance

During the Middle Ages, music was dominated by the church modes. The Ionian mode was initially considered too "lascivious" for sacred music but gained acceptance over time. By the Renaissance, theorists like Gioseffo Zarlino began to champion the Ionian (major) and Aeolian (minor) modes as the most harmonically stable, laying the groundwork for tonality.

The Baroque Period and the Consolidation of Tonality

The Baroque era (1600-1750) was the turning point. The major-minor system became the standard language of music. The development of equal temperament—a tuning system that allowed music to sound good in any key—cemented the major scale's dominance. J.S. Bach's "The Well-Tempered Clavier," a collection of pieces in all 24 major and minor keys, is the ultimate monument to this new system.

Classical, Romantic, and Beyond

Throughout the Classical (1750-1820) and Romantic (1820-1900) periods, composers like Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms used the major scale as the foundation for complex musical forms like the sonata and the symphony. While 20th-century composers began to explore atonality and other systems, the major scale never lost its power. In jazz, pop, rock, and film music, it remains an essential, unshakable foundation.

The Major Scale on Different Instruments

Piano and Keyboards

On the piano, each major scale has a unique visual pattern of white and black keys, but the fingering patterns are designed for efficiency. For example, the C Major scale fingering is standard:

Right Hand: 1-2-3-1-2-3-4-5 (thumb crosses under after the 3rd finger)

Left Hand (descending): 1-2-3-1-2-3-4-5 (3rd finger crosses over the thumb)

Practicing these standardized fingerings is key to playing smoothly in all keys.

Guitar

On the guitar, a single major scale can be played in many different positions on the fretboard. A common way to learn these is through movable "box" patterns. The CAGED system is a popular method that organizes the fretboard into five interconnected scale shapes based on the open chord shapes of C, A, G, E, and D. Here is one common pattern for the C major scale:

e|---------------------------------5-7-8-| B|---------------------------5-6-8-------| G|---------------------4-5-7-------------| D|---------------5-7---------------------| A|---------------------------------------| E|---------------------------------------|

Mastering these patterns allows a guitarist to play in any key simply by moving the same shape to a new starting fret.

Wind Instruments

For instruments like the flute, clarinet, saxophone, or trumpet, major scales are played with specific fingerings or valve combinations. Systematic scale practice is critical for developing not only finger dexterity but also breath control, consistent tone quality, and accurate intonation across the instrument's entire range.

String Instruments

On non-fretted string instruments like the violin, viola, or cello, playing major scales is the primary way to train intonation (playing in tune). Since there are no frets, the musician must develop precise muscle memory in the left hand. This requires careful coordination with the right hand (the bow) to produce a clean, even tone for each note of the scale. Practice often involves shifting the hand to different positions on the fingerboard to play scales over multiple octaves.

Musical Applications of the Major Scale

Melody

Most of the melodies we recognize are built from the notes of a major scale. Melodies often move by step (conjunct motion) or by leaping between scale notes (disjunct motion). A well-crafted melody typically creates a sense of journey and returns to the tonic for a feeling of closure. The song "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" is a perfect example of a melody built entirely from a major scale.

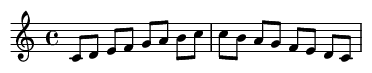

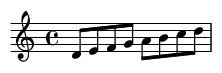

Example: A Familiar Melody in C Major

Harmony

The major scale is the bedrock of tonal harmony. The seven diatonic chords (I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, vii°) derived from it are the building blocks for chord progressions. Certain progressions have become staples of Western music due to their powerful and pleasing sound:

- I-IV-V-I: The foundation of countless folk, blues, and classical pieces.

- I-V-vi-IV: The "four-chord song" progression used in hundreds of pop hits.

- ii-V-I: The most important chord progression in all of jazz.

- I-vi-IV-V: The classic "doo-wop" progression of the 1950s.

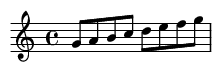

Example: I-IV-V-I Progression in C Major

Improvisation and Composition

For both composers and improvisers, the major scale is home base. It provides a reliable palette of notes that are guaranteed to sound "correct" over the diatonic chords of a key. Mastering the major scale in all 12 keys is a prerequisite for creative freedom, allowing a musician to move seamlessly between melody and harmony in any musical situation.

The Modes of the Major Scale

If you take the notes of a major scale but start and end on a different degree, you create a new scale with a unique mood and color. These are called modes. Each major scale contains seven modes:

- Ionian (from the 1st degree) : The major scale itself (bright, happy).

- Dorian (from the 2nd degree): A minor-sounding mode with a "jazzy" major 6th (moody, thoughtful).

- Phrygian (from the 3rd degree): A minor-sounding mode with a "Spanish" or "flamenco" minor 2nd (dark, exotic).

- Lydian (from the 4th degree): A major-sounding mode with a "dreamy" or "celestial" sharp 4th.

- Mixolydian (from the 5th degree): A major-sounding mode with a "bluesy" flat 7th (common in rock and blues).

- Aeolian (from the 6th degree): The natural minor scale (sad, romantic).

- Locrian (from the 7th degree): A dissonant, tense-sounding mode, used less commonly.

Learning modes opens up a vast new world of melodic and harmonic possibilities beyond the standard major/minor sound.

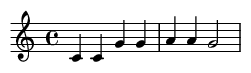

Example: D Dorian Mode (the notes of C major, from D to D)

Practical Exercises for Mastery

Exercise 1: Cycle Through the Keys

Practice playing your major scales by following the circle of fifths. Start with C, then move to G (adding F#) , then D (adding C#), and so on. Then go the other way: C, F (adding Bb), Bb (adding Eb), etc. This builds muscle memory and solidifies your knowledge of key signatures.

Exercise 2: Practice in Intervals

Don't just play scales up and down. Practice them in melodic intervals, such as thirds. This trains your ear and fingers to navigate the scale more fluidly.

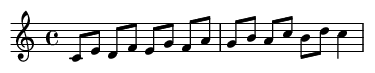

Example: C Major in Diatonic Thirds

Exercise 3: Guided Improvisation

Record yourself playing a simple I-IV-V-I chord progression, or find a backing track online. Then, improvise a melody over it using only the notes of the corresponding major scale. Start simple, then experiment with different rhythms and patterns. This directly connects the technical practice of scales to the creative act of making music.

Beyond the Major Scale

Mastering the major scale is the gateway to understanding a wider universe of musical sounds. Once you are comfortable with it, you can explore:

- Minor Scales: The natural minor (Aeolian mode) , harmonic minor, and melodic minor scales offer darker, more dramatic colors.

- Pentatonic Scales: Five-note scales (like C-D-E-G-A) that are incredibly versatile and common in rock, blues, and folk music.

- Blues Scales: A six-note scale with a characteristic "blue note" that defines the sound of the blues.

- Exotic and Synthetic Scales: The whole-tone scale, diminished scales, and scales from musical traditions around the world offer even more expressive palettes.

Conclusion:

The major scale, with its simple pattern of whole and half steps, is far more than a technical exercise; it is the DNA of Western music. Its structure has profoundly shaped our collective understanding of melody, harmony, and musical form, providing the framework for masterpieces across every genre and era.

From its seven notes, we derive a rich harmonic system, a spectrum of expressive modes, and the very sense of tension and release that makes music emotionally compelling. Its balanced, consonant structure creates a sense of "home" that resonates with listeners everywhere.

For any musician, mastering the major scale is not about rote memorization. It is about internalizing the fundamental language of music. It is the key that unlocks the fretboard, the keyboard, and the rulebook of harmony. For the composer, it is a timeless tool for expression. For the listener, understanding its function transforms hearing into active listening, revealing the elegant architecture that holds up the music we cherish.

In a world of infinite sonic possibilities, the major scale remains our most enduring and essential point of reference—a testament to its perfect blend of elegant simplicity and inexhaustible creative potential.

References:

-

Kostka, S., Payne, D., & Almén, B. (2017). "Tonal Harmony" (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

-

Levine, M. (1995). "The Jazz Theory Book". Sher Music Co.

-

Persichetti, V. (1961). "Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice". W. W. Norton & Company.

-

Benward, B., & Saker, M. (2014). "Music in Theory and Practice" (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.