Unlocking Harmonic Journeys: A Guide to the Extended II-V Progression

b4n1

June 14, 2025, 7:04 p.m.

Unlocking Harmonic Journeys: A Guide to the Extended II-V Progression

Summary:

This article delves into the Extended II-V progression, a fundamental concept in jazz and modern harmony. We'll explore how this chain of chords creates compelling forward motion, adds harmonic sophistication to music, and serves as a powerful tool for both composers and improvisers. By understanding its structure and application, musicians can unlock new levels of creativity in their playing and writing.

Keywords:

Extended II-V, jazz harmony, chord progressions, circle of fifths, secondary dominants, functional harmony, music theory, improvisation, reharmonization.

Introduction:

If you've spent any time studying jazz, you've undoubtedly encountered the mighty II-V-I progression. It's the harmonic bedrock of countless standards, providing a satisfying cycle of tension and release. But what happens when we want to prolong that journey? What if we could create a "harmonic runway" that builds even more anticipation before landing at our destination? This is precisely where the Extended II-V comes in. It's a sequence of connected II-V pairs that guide the listener through a series of temporary key centers, creating a rich, flowing, and dynamic sound that is quintessentially jazz.

Definition and Classification:

An Extended II-V is a sequence of chords where multiple II-V pairs are chained together before the final resolution to a I chord. The V chord of one pair typically resolves to the II chord of the next pair, which is a perfect fourth above (or a perfect fifth below). This motion beautifully follows the circle of fifths in a counter-clockwise direction, creating strong, predictable root movement.

We can classify them into a few types:

1. Chromatic (Secondary Dominant) Extended II-V: This is the most common and powerful type. Each V chord in the chain is altered to be a dominant 7th chord, acting as a "secondary dominant" that pulls strongly to the next II chord, even if that chord is outside the home key. This creates a cascade of resolutions.

2. Diatonic Extended II-V: In this version, all chords are derived strictly from the parent key's scale. While it provides smooth voice leading, the pull between chords is weaker because not all the "V" chords will be dominant 7ths. For example, in C major, a III-VI-II-V would be Em7-Am7-Dm7-G7, where the Am7 is not a dominant chord.

3. Turnarounds: Extended II-Vs are frequently used as turnarounds, with the most famous being the III-VI-II-V progression. This can be analyzed as a II-V pair leading to the primary II chord. In C major: [Em7(ii of Dm7) - A7(V of Dm7)] leads to [Dm7(ii of C) - G7(V of C)].

Examples:

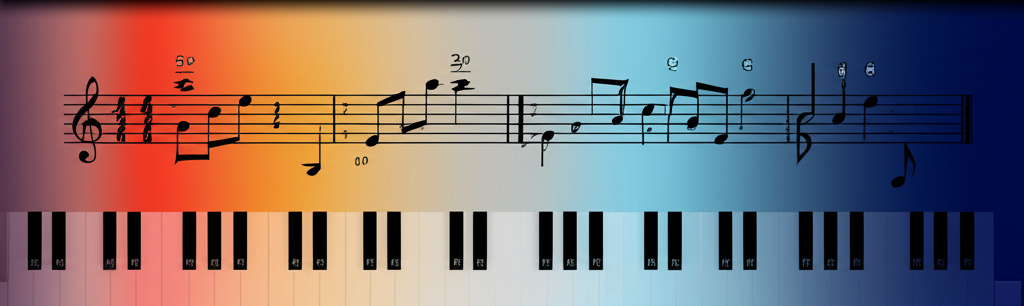

Example in ABC Notation:

Here is a classic extended II-V progression in the key of C Major. It begins with the II-V of D minor (Em7 - A7), which then leads into the primary II-V of C Major (Dm7 - G7), before finally resolving to the tonic (Cmaj7). Notice how the A7 contains a C# to make it a true dominant, pulling strongly to the Dm7.

Notación musical:

Practical Applications:

The extended II-V is not just a theoretical concept; it's everywhere in practice. It's a favorite device for composers and arrangers to add harmonic interest and movement, especially in introductions, bridges, and turnarounds. For improvisers, recognizing these chains is crucial. Instead of seeing a bewildering series of chords, a soloist can "chunk" them into II-V units, simplifying their melodic approach. Many jazz standards are built around this device. The bridge of Jerome Kern's "All The Things You Are" features a famous sequence of II-Vs, and Antonio Carlos Jobim's "How Insensitive" uses a descending chromatic II-V chain to create its signature melancholic mood. Miles Davis's tune "Tune Up" is a brilliant study in II-V-I progressions in three different keys.

Historical Figures:

The popularization of complex harmony like the extended II-V is deeply tied to the Bebop revolution of the 1940s. Musicians like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were pioneers, using these intricate progressions as vehicles for their virtuosic improvisations. They would often reharmonize older, simpler standards with these sophisticated chains. Later, pianist and composer Thelonious Monk took harmonic exploration to another level with his unique and angular approach. But perhaps no one pushed the boundaries of sequential harmony further than saxophonist John Coltrane. His famous "Coltrane Changes," as heard on "Giant Steps," are a hyper-extended and substituted form of these progressions, cycling through keys related by major thirds. These artists weren't just playing chords; they were architects of sound, using harmony to build new worlds.

Fun Facts:

The concept of sequential harmony isn't exclusive to jazz. If you listen closely to the works of J.S. Bach, you'll hear the same principles at play! His use of descending fifths sequences in fugues and inventions is a clear baroque ancestor to the modern extended II-V. Think of the extended II-V as a "harmonic rollercoaster." Each II-V is a small hill and drop, building momentum and excitement before the ride finally glides into the station (the tonic chord). This cascading feeling is a direct result of the root movement following the powerful pull of the circle of fifths.

Conclusions:

The extended II-V progression is more than just a string of chords; it's a narrative device. It creates a sense of journey, expectation, and ultimate satisfaction. By chaining together the fundamental tension-and-release engine of the II-V, composers and improvisers can craft more sophisticated and compelling musical stories. Mastering this concept opens the door to a deeper understanding of harmonic movement and is an essential step for any musician looking to master the language of modern music. As a final thought, how can you use this device in your own music? Try taking a simple progression and see where you can insert an extended II-V to lead into one of your chords.

References:

Levine, M. (1995). The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.

Coker, J. (1997). Patterns for Jazz: A Theory Text for Jazz Composition and Improvisation. Alfred Music.

Aebersold, J. (n.d.). The II/V7/I Progression. Retrieved from: https://www.jazzbooks.com