The Dominant Eleventh Chord: A Guide to Its Sound, Soul, and Function

b4n1

June 14, 2025, 7:04 p.m.

The Dominant Eleventh Chord: A Guide to Its Sound, Soul, and Function

Summary:

This article dives deep into the dominant eleventh chord (V11), a rich and complex harmony that adds color and tension to music. We will explore its theoretical construction, common voicings, and its vital role in genres from Impressionism to jazz and funk. Understanding the V11 is key to unlocking a more sophisticated harmonic vocabulary.

Keywords:

Dominant Eleventh, V11 Chord, Extended Chords, Music Theory, Jazz Harmony, Funk Chords, Chord Voicing, Harmonic Tension, Suspended Chords

Introduction:

Have you ever heard a chord that feels both suspended in mid-air and brimming with energy, pushing the music forward? You may have been hearing the dominant eleventh chord. Far more than just another stack of thirds, the V11 is a chameleon of harmony. In its full form, it contains a spicy dissonance that demands attention. Yet, in its most common voicings, it offers a cool, floating quality that has become a staple of jazz, funk, and modern pop. This article will demystify this fascinating chord, showing you how to build it, use it, and appreciate its unique place in the musical landscape.

Definition and Classification:

A dominant eleventh chord is a six-note chord built on the fifth degree (the dominant) of a major or minor scale. It's an extended chord, meaning it goes beyond the basic seventh by adding the ninth and the eleventh. The complete formula, based on the root (R), is: Root - Major Third - Perfect Fifth - Minor Seventh - Major Ninth - Perfect Eleventh (R - 3 - 5 - b7 - 9 - 11). For a G11 chord (the dominant of C major), the notes would be G - B - D - F - A - C.

The most crucial feature of the complete dominant eleventh chord is the harsh dissonance created between its major third and the perfect eleventh. In our G11 example, this is the interval between B and C—a minor ninth. Because of this clash, this full voicing is rare. In practice, the chord is almost always modified in one of two ways:

1. The Common V11 (with an omitted 3rd): This is the most widely used version of the chord. By removing the third, the clash disappears, leaving a stable, open-sounding chord. A G11 without the B (G-D-F-A-C) sounds very similar to an F major triad over a G in the bass (F/G). This is often thought of as a G7sus4 with an added 9th.

2. The Altered V7#11: To avoid the minor ninth clash while keeping the third, composers and improvisers often sharpen the eleventh. This creates a V7#11 chord (e.g., G-B-D-F-A-C#). This "Lydian Dominant" sound is bright and sophisticated, and is a cornerstone of modern jazz harmony.

Examples:

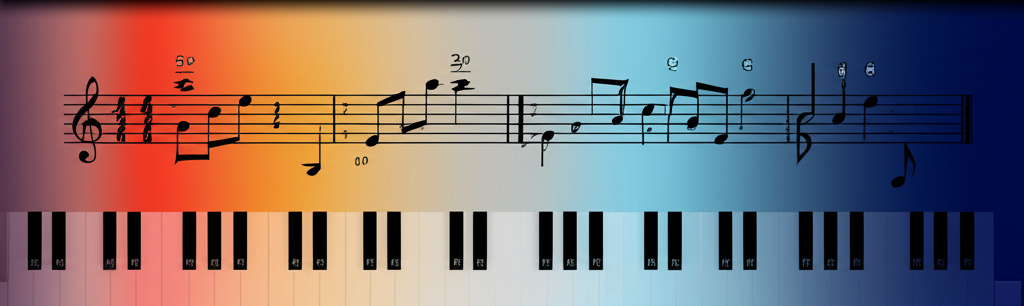

Example in ABC Notation:

Here we see two voicings of a dominant eleventh. The first is a complete C11 chord, where you can see all six notes. Note the theoretical clash between the third (E) and the eleventh (F). The second example is a much more common, practical voicing for a G11 chord resolving to C major. Notice the third (B) is omitted, creating a classic "sus" sound that resolves smoothly.

Notación musical:

Practical Applications:

The dominant eleventh is a versatile tool. In traditional functional harmony, its role is to create tension that resolves to the tonic (I) chord. The common voicing (without the 3rd) essentially acts as a powerful V7sus4, delaying the arrival of the leading tone and softening the resolution. This is extremely common in jazz standards and gospel music. You can hear this sound all over Herbie Hancock's iconic album "Maiden Voyage." In funk and R&B, the dominant eleventh is often used non-functionally as a static harmonic color. Think of the vamps in songs by James Brown or Stevie Wonder; the V11 provides a groovy, percussive harmonic bed that doesn't need to resolve, it just needs to feel good.

Historical Figures:

While extended chords existed in theory, it was the French Impressionists who began to untether them from their functional roles. Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was a master of using harmonies for their sheer color and atmosphere. He would use eleventh chords not just as dominants, but as floating, unresolved sonorities that painted a picture, a radical departure from the Germanic tradition. Later, in the world of jazz, pianist and composer Herbie Hancock (b. 1940) redefined the role of the chordal instrument. With Miles Davis's Second Great Quintet and on his own solo records, Hancock championed the use of suspended and eleventh chords. He stripped them of their traditional "must-resolve" function and used their open, ambiguous quality to create a new, interactive, and modern improvisational language.

Fun Facts:

The easiest way to think about and play a common dominant eleventh chord is the "slash chord" trick. A G11 (without the 3rd) is simply an F major triad played over a G bass note (F/G). A C11 is a Bb/C. This shortcut is used by pianists and guitarists everywhere to quickly access the cool, modern sound of this chord without getting bogged down in theory. For centuries, traditional harmony textbooks either forbade the use of the complete dominant eleventh or treated it as a theoretical anomaly due to the B-C clash (in the key of C). Its widespread acceptance and creative use is a testament to how harmony has evolved!

Conclusions:

The dominant eleventh chord is a perfect example of musical evolution. Once considered problematic or even "incorrect," it has become an indispensable tool for creating rich harmonic textures. It embodies both tension and serene suspension, depending on its voicing. As a musician, understanding both its complete theoretical form and its practical, modified versions gives you access to a spectrum of colors, from the biting dissonance of its full form to the cool, smooth sound that has defined genres. The next time you sit at your instrument, try playing a V11 chord instead of a standard V7. How does it change the feeling of the progression?

References:

Levine, M. (1995). The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.

Tymoczko, D. (2011). A Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice. Oxford University Press.

Nettles, B. & Graf, R. (2007). The Chord Scale Theory & Jazz Harmony. Berklee Press.