Common Chord Progressions: The Building Blocks of Musical Harmony

b4n1

May 17, 2025, 4:26 p.m.

Common Chord Progressions: The Building Blocks of Musical Harmony

Summary:

Chord progressions are the harmonic foundations that drive musical compositions across nearly all Western musical styles. This comprehensive guide explores the most common and influential chord progressions, from the classic I-IV-V pattern to more complex sequences found in jazz and contemporary music. Understanding these fundamental harmonic pathways illuminates how composers create emotional journeys, build tension and release, and establish musical coherence. Whether you're a songwriter, composer, music producer, or analytical listener, mastering these common progressions opens endless creative possibilities while deepening your appreciation of the music you love.

Keywords:

chord progressions, harmony, cadences, I-IV-V, ii-V-I, circle of fifths, chord sequences, functional harmony, diatonic chords, song structure, musical composition

Introduction:

At the heart of nearly every memorable song lies a compelling chord progression—a deliberate sequence of chords that creates movement, emotional resonance, and musical logic. Chord progressions are the highways along which melodies travel, the foundations upon which musical stories are built, and the invisible structures that guide listeners through sonic landscapes.

While melodies might be what we sing and rhythms what we tap our feet to, chord progressions are what make our hearts swell, creating those moments of tension, surprise, and satisfying resolution that define our emotional connection to music. From the simplest three-chord folk song to the most sophisticated jazz composition, chord progressions establish the harmonic context that gives meaning to every other musical element.

In this article, we'll explore the most common and influential chord progressions that have shaped Western music, examining why they work, how they're used across different genres, and how understanding them can transform your appreciation of music whether you're creating it or simply enjoying it.

Understanding Chord Functions

Before diving into specific progressions, it's essential to understand that chords in a progression aren't just random choices—they serve specific functions related to how they create and resolve tension.

The Three Primary Chord Functions

- Tonic (I): The "home" chord that provides stability and resolution. In the key of C major, this is a C major chord.

- Subdominant (IV): Creates gentle movement away from the tonic, introducing mild tension. In C major, this is an F major chord.

- Dominant (V): Generates strong tension that seeks resolution back to the tonic. In C major, this is a G major chord.

Additional functional roles include:

- Predominant chords (ii, IV, vi): Typically lead to the dominant, preparing the listener for that tension.

- Substitute chords: Can replace primary function chords while maintaining similar harmonic roles (for example, vi can substitute for I as they share two notes).

- Passing chords: Create smooth voice-leading between functional harmonies.

Understanding these functional relationships helps explain why certain progressions sound satisfying—they follow natural patterns of tension and resolution that our ears have become accustomed to through centuries of musical tradition.

The Most Common Chord Progressions

I-IV-V: The Foundational Progression

The I-IV-V progression is perhaps the most fundamental chord sequence in Western music, forming the backbone of blues, rock, folk, country, and countless pop songs.

In C major, this progression would be:

- C major (I) - F major (IV) - G major (V)

This progression works because it outlines the core functions of tonal harmony: stability (I), movement away from stability (IV), and tension seeking resolution (V), typically resolving back to I.

Famous examples include:

- "Sweet Home Alabama" by Lynyrd Skynyrd

- "La Bamba" by Ritchie Valens

- "Twist and Shout" by The Beatles

- Countless blues songs using the 12-bar blues format

Variations include repeating certain chords or changing their order (I-V-IV-I), but the functional relationship remains intact.

I-V-vi-IV: The Pop Progression

Often called the "pop-punk progression" or "sensitive female chord progression," this sequence has dominated popular music for decades.

In C major, this would be:

- C major (I) - G major (V) - A minor (vi) - F major (IV)

This progression works well because it creates a perfect balance of emotions: the stability of I, the tension of V, the relative sadness of vi, and the gentle pull of IV leading back to I.

Famous examples include:

- "Let It Be" by The Beatles

- "Don't Stop Believin'" by Journey

- "Under the Bridge" by Red Hot Chili Peppers

- "Africa" by Toto

The same chords can be rearranged (vi-IV-I-V) for a progression that starts with the relative minor, creating a more melancholic feel while maintaining the same harmonic palette.

ii-V-I: The Jazz Essential

The ii-V-I progression forms the foundation of jazz harmony and appears frequently in other sophisticated popular music styles.

In C major, this would be:

- D minor 7 (ii) - G dominant 7 (V) - C major 7 (I)

This progression exemplifies functional harmony at its most elegant: the ii chord serves as a predominant function, setting up the dominant V chord, which then resolves to the tonic I. The addition of 7th chords creates richer harmonies and smoother voice leading between chords.

Famous examples include:

- "Autumn Leaves" (in the relative minor: i-VII-III)

- "All The Things You Are" (features multiple ii-V-I sequences)

- "Take the 'A' Train" by Duke Ellington

- Countless jazz standards

In jazz contexts, this progression is often extended with substitutions and additional chords, but the functional core remains the same.

I-vi-IV-V: The 50s Progression

This progression dominated early rock and roll, doo-wop, and pop music in the 1950s and early 1960s.

In C major, this would be:

- C major (I) - A minor (vi) - F major (IV) - G major (V)

This progression creates a perfect vehicle for storytelling with its predictable harmonic journey: beginning with stability, introducing an emotional shift with the relative minor, moving further away with the subdominant, and then building tension with the dominant that begs to be resolved back to the tonic.

Famous examples include:

- "Stand By Me" by Ben E. King

- "Earth Angel" by The Penguins

- "Duke of Earl" by Gene Chandler

- "Unchained Melody" by The Righteous Brothers

Examples:

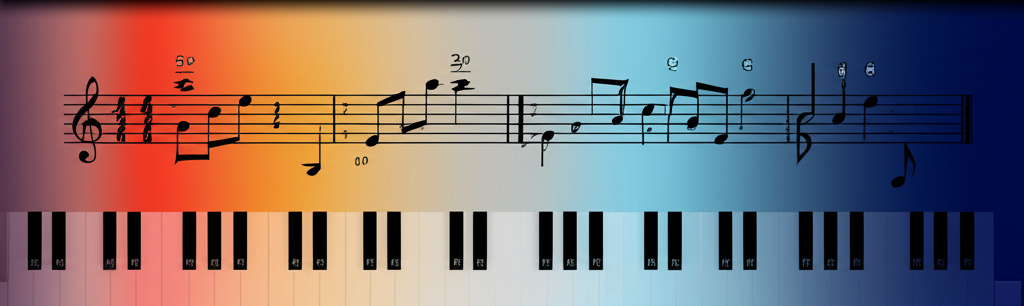

Example in ABC Notation:

A simple I-IV-V-I progression in C major:

A ii-V-I progression in jazz style (C major):

Advanced Progressions and Variations

Circle of Fifths Progression

The circle of fifths progression follows the natural harmonic movement where each chord's root note is a fifth below (or a fourth above) the previous chord.

A diatonic circle progression in C major might be:

- C major (I) - F major (IV) - B diminished (vii°) - E minor (iii) - A minor (vi) - D minor (ii) - G major (V) - C major (I)

More commonly, portions of this circle are used, such as the vi-ii-V-I progression (Am-Dm-G-C in C major), which creates a smooth harmonic flow due to the strong relationship between chords a fifth apart.

Famous examples include:

- "Autumn Leaves" (partial circle of fifths)

- Bach's "Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major" (employs circle progressions)

- "My Funny Valentine" (contains segments of descending fifths)

Modal Interchange

Modal interchange (or modal mixture) borrows chords from the parallel minor or other modes to add color and emotional depth to progressions.

A simple example in C major might be:

- C major (I) - Ab major (♭VI) - F major (IV) - G major (V)

Here, the Ab major chord is borrowed from C minor (or the parallel Aeolian mode), creating a surprising and emotionally rich moment that enriches the otherwise diatonic progression.

Famous examples include:

- "Creep" by Radiohead

- "Space Oddity" by David Bowie

- "Penny Lane" by The Beatles

Descending Bass Lines

Many effective progressions use stepwise descending bass lines to create smooth, compelling movement.

In C major, a classic descending progression might be:

- C major (I) - G/B (V/9) - Am (vi) - F/A (IV/6) - F (IV) - C/E (I/3) - D minor (ii) - G (V)

The bass line C-B-A-A-F-E-D-G creates a natural descent that pulls the listener through the progression. The voice leading in the other chord tones typically moves minimally, creating coherence.

Famous examples include:

- "My Funny Valentine"

- "Stairway to Heaven" by Led Zeppelin (opening section)

- "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" by The Beatles

Cadences: The Punctuation of Harmony

Cadences are specific chord progressions that function like musical punctuation, marking the end of phrases or sections. The four main types of cadences are:

- Perfect (Authentic) Cadence (V-I): Creates a strong sense of resolution, like a musical period. Example: G major to C major in the key of C.

- Plagal Cadence (IV-I): Often called the "Amen cadence," creates a gentler resolution. Example: F major to C major in the key of C.

- Imperfect Cadence (any chord to V): Creates an unresolved feeling, like a musical question mark. Example: C major to G major in the key of C.

- Interrupted (Deceptive) Cadence (V-vi): Subverts expectations by moving to the relative minor instead of resolving to I. Example: G major to A minor in the key of C.

Composers use these cadential formulas to establish structure, create or resolve tension, and shape the listener's experience of musical form.

Genre-Specific Progressions

Blues: The 12-Bar Form

The 12-bar blues progression is one of the most influential chord sequences in American music:

In C, the traditional 12-bar blues follows this pattern:

- I (C7) for 4 bars

- IV (F7) for 2 bars

- I (C7) for 2 bars

- V (G7) for 1 bar

- IV (F7) for 1 bar

- I (C7) for 2 bars

In jazz contexts, this basic form is often enhanced with additional chords and substitutions, but the essential structure remains recognizable.

Jazz: Rhythm Changes

"Rhythm changes" refers to the chord progression from George Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm," which became a foundational form for countless jazz compositions.

The basic structure in Bb major consists of:

- A section: I-VI-ii-V | I-VI-ii-V | I-I7-IV-#iv° | I-V-I

- B section (bridge): III-III7-VI-VI7 | II-II7-V-V7

This sophisticated progression has served as the foundation for hundreds of jazz compositions, including "Oleo" by Sonny Rollins and "Anthropology" by Charlie Parker.

Rock: Power Chord Progressions

Rock music often employs simplified chord structures, frequently using power chords (root and fifth only, no third) to create a raw, powerful sound.

Common rock progressions include:

- I-♭VII-IV (e.g., E-D-A in E, as used in "Sweet Child O' Mine" intro)

- I-♭VI-♭VII (e.g., E-C-D in E, as in "Enter Sandman" by Metallica)

- i-♭VII-♭VI-i (e.g., Em-D-C-Em, as in "Nothing Else Matters" by Metallica)

These progressions often employ modal interchange, borrowing chords from parallel modes to create the characteristic "heavy" sound of rock and metal.

Applying Chord Progressions in Composition

When working with chord progressions in your own compositions, consider these principles:

- Functional balance: Effective progressions generally balance movement away from the tonic with resolution back to it.

- Voice leading: The most natural-sounding progressions feature smooth movement between individual notes in each chord.

- Emotional arc: Chord progressions can create emotional journeys by managing tension and release.

- Subverting expectations: Surprising chord changes can create memorable moments when they break from established patterns.

- Repetition and variation: Repeating a progression creates familiarity, while slight variations maintain interest.

Remember that these common progressions are starting points—feel free to experiment with alterations, extensions, and substitutions to develop your unique harmonic voice.

Conclusion:

Chord progressions are far more than just theoretical constructs—they're the emotional engines of music, driving our experience as listeners and providing the framework for melodic expression. The progressions we've explored have shaped centuries of musical development, appearing across genres and eras because they tap into fundamental principles of tension, release, and harmonic movement.

While these common progressions provide reliable templates for creating effective music, the most exciting compositions often come from thoughtful variations and combinations of these established patterns. Understanding these progressions gives you both a roadmap of what has worked in the past and a foundation from which you can create your own harmonic journeys.

Whether you're analyzing your favorite songs, composing new music, improvising over changes, or simply developing a deeper appreciation for the music you hear, recognizing these common chord progressions opens up new dimensions of musical understanding and enjoyment.

References:

-

Levine, Mark. "The Jazz Theory Book." Sher Music Co., 1995.

-

Schoenberg, Arnold. "Theory of Harmony." University of California Press, 1983.

-

Tagg, Philip. "Everyday Tonality." The Mass Media Music Scholars' Press, 2014.

-

Stephenson, Ken. "What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis." Yale University Press, 2002.